Building off the success of his wonderfully deranged ‘Barbarian’ (2022), Cregger returns with a flawed but fun-filled horror-mystery aimed at the lethal spell of smartphones

Among the many Simpsons taglines instantly recognisable to the average TV-obsessed millennial, Helen Lovejoy’s “Think of the children!!” might not sit at the top of the list. Regardless, so totemic of her role as Springfield’s resident hysterical mother-figure, the quote is but one of many child safety-fearing cliches familiar to us all. And it’s the cliche which must have been present in the mind of millennial director Zach Cregger when penning his mystery-horror and box office hit Weapons, which — honing in on events following the mysterious disappearance of 17 young school kids one school night in the fictional town of Maybrook, Pennsylvania — places children front and centre in its story.

Yet it does so despite the fact that children remain largely absent from the film’s action, focusing attention instead on the puerile, dysfunctional lives of Maybrook’s supposedly responsible adults. Suitably, children in Weapons embody a pointedly ghost-like air, a presence in absentia Cregger makes plain through the film’s opening sequence.

A formidable overture, the first five minutes or so of Weapons cement the film as a modern-day Brothers Grimm aimed not at children, but their parents and guardians. We open with a black screen, over which an anonymous young girl begins narrating the events, once-upon-a-time-style, surrounding the disappearance. Framing what we’re about to see as a fable you’d do well to heed, the youthful innocence of her voice is suitably shot with a clarity that commands attention, thus reversing the traditional parent-child roles of the bedtime story read. Already we’re asked: Parents, are you listening?

We subsequently see a montage of the affair as she recounts the details of the mystery — the disappearance, the rush to investigate, the police failures — before, at last, the girl’s words come to overlay flashbacks of the 17 missing children fleeing into the night. As we witness the strangely ethereal-looking children slip out from their homes and race giddily into the dark, their arms uniformly spread aeroplane-style, it’s no coincidence that George Harrison’s “Beware of Darkness” plays out; a wistful hymn to youth tinged with innocence and forewarning, its cautionary, haunting lyrics urging us to beware the night will echo throughout the entirety of Weapons.

The film begins in earnest two months on from the disappearance, when little remains known about what happened in the wee hours of that Wednesday morning. All we have to go on is that the children were seen running out of their home into the thick of darkness at 2.17am exactly (details we know thanks to the Ring camera footage of bereft parents), and that chief suspect, for lack of any other leads, is their teacher, Miss Justine Gandy (Julia Garner). Another niggling detail is that out of Justine’s class of disparus, one child mysteriously remains: the taciturn young Alex Lilly (Cary Christopher), who we suspect knows more.

The scene is set, in theory, for a forward-moving horror-whodunit. However, instead of launching into a chronological structure we might expect from a mystery, Cregger honours his title as chief narrative shaker-upper by plunging us into a nonlinear, multi-perspective extravaganza made up of overlapping sub-stories — all seamlessly shot with his signature blend of gonzo horror and deranged humour.

Each sub-narrative belongs to a specific character and unfolds within their own titled chapter (conjuring Stephen King’s IT). Frequently revisiting scenes from different pairs of eyes, Weapons folds together satisfyingly like a complex work of origami to reveal an infallibly linked-up world, eventually converging towards the film’s conclusion. (Film buffs might recall Sidney Lumet’s 2007 Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, which employs a similar format to narrate cash-strapped brothers Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman in their caperish, ill-fated plans to rob the family jewellery store).

The first “chapter” is dedicated to teacher Justine, whose life is stalked by accusations and anger in the wake of the disappearance. Parents of the missing pupils have united their witch hunt-style campaign against her, who, in order to cope, has resorted to booze. Between work and nightly binges — which spill into each other with as much ease as she pours vodka into her Big Gulps — Justine busies herself with finding out more about remaining child Alex, believing he holds answers. It’s when she finally follows his home from school one afternoon and stalks to the perimeter of his home (whose ground floor windows are ominously blacked out with newspaper) that Justine gets a clue she must delve deeper: the sight of Alex’s catatonic parents seated in the darkened, fusty living room.

Later, we walk a mile in the shoes of parent Archer Graff (Josh Brolin), the self-appointed leader of the campaign against teacher Justine whom, driven by rage, he publicly brandishes as the culprit by spray-painting “witch” along the side of her car. Haunted by the disappearance of his son Matthew, Archer obsesses over the details of what took place that night — sleeping in Matthew’s bed, hounding the local police department and pouring over the Ring footage of Matthew’s 2.17am night flight. Watching it late one evening, Archer (rather tardily?) concludes that by using his skills as a contractor, and by viewing the camera footage of other afflicted parents, he can determine the direction in which the missing children were heading as they flew out into the night from their homes.

Spiralling outwards from here, Weapons expands to include characters not directly involved in the disappearance. Those yet to see the film can perhaps guess at how characters might overlap based purely on their occupation and social standing: there’s the sometime lover of Justine, betrothed cop and recovering alcoholic Paul Morgen (Alden Ehrenreich); the young vagrant James (Austin Abrams), whose comedy-of-errors exploits emphasise a certain crime-caper element of the film (and which, unsurprisingly, land him in a whole world of trouble); and the kindhearted principal and ally to Justine, Marcus Miller (Benedict Wong).

Amongst the business, Cregger anchors the movie through Justine and Archer, the pair (just about) dominating screen time and “starring” the film. Naturally, despite starting out as enemies, fortune has it that Justine and Archer orbit ever closer to one another across overlapping sub-narratives of other, more constellated characters, eventually uniting in their search for answers.

If only they knew what we knew — that pulling the strings of it all, as we quickly suspect, is the refreshingly sinister clown-figure that is Gladys (Amy Madigan). Cropping up with more and more frequency across narrative strands as the film progresses, Gladys is a protean, wily villain who first appears in full-clown mode to haunt dreams, outdoor spaces and even bedroom ceilings.

Later, however, we’re introduced to her second, diluted iteration, a by-day disguise: the varicoloured accessorizer with giant designer shades, a Birkin-style purse and an immaculate red hairdo sporting an impossibly cropped, Berghain-giving fringe. These are features off-set by her overtly bumbling, faux-naïf demeanour. Yet, like the fringe, her visibly distressed clownish lips hint at something sinister, but which, lost in the charismatic chaos of her get-up, is somehow blurred.

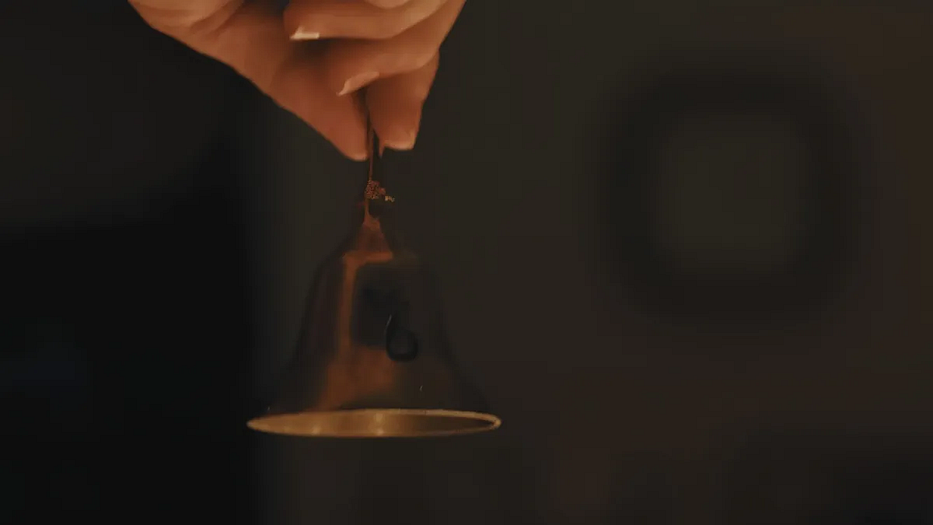

It’s with her bewitching guise that Gladys penetrates schools and homes in order to influence and deter those treading too close to the truth: that she’s behind the disappearance of Miss Gandy’s class. In actual fact a fetish-wielding witch, Gladys draws upon her powers of magic to entrance others for her own gain — including the lives of 17 children, whose youthful vitality she feeds from in order to survive — whilst recruiting others, mostly adults, as her personal catatonic killing machines.

It’s clear that through Gladys and her powers of possession, Cregger is tapping into the indoctrination and potential weaponisation of today’s smartphone-hooked youth, and the parental blindness, or catatonia, that enables it. Indeed, disguised as a clown (tempered or otherwise), Gladys functions as a relic, an old-school ghoul recoded with the contemporary signifiers of the smartphone and the Big Tech world behind it. (Note also the similarity in spelling between the names Gladys and Miss Justine Gandy, a resemblance that scores society’s eternal conflation between easy target/genuine perpetrator, our inevitable blindness to the real issue at hand).

Just take her use of the designer purse alone, from which she ritualistically retrieves her magic fetish and more, ready to render unsuspecting victims catatonic. For me, Gladys’ purse — and her use of it — is a sly nod to the popular What’s in My Bag videos of social media, vacuous content in which A-listers showcase their various bits and bobs from sanitisers and supplements to Airpods and personal charms. Highly fetishised objects, their day-to-day paraphernalia are imbued with a class-tinged, profoundly consumerist mysticism that speaks to something slightly unsettling but hypnotically (and regrettably) watchable.

Like Gladys, celebrity “baggers,” for want of a term, mimic the image of the touring clown equipped with his or her own Mary Poppins-style bag of tricks. Crucially, clowns exist on a blurred line between that which amuses and scares, entices and influences. They’re paradoxical entities once believed to be adored by children (and harmless to them), but which today are commonly accepted as neither.

Couldn’t smartphones — and more specifically the worlds they open up to users — be said to fulfill a similar function? Like clowns, they can all at once distract, beguile, terrify and sadden. And as clowns once were, they continue to be tolerated, permitted to inhabit the lives of children today only now equipped with AI software able to conjure up infinite amounts of chilling uncanniness through its powers of generative production (perhaps the ultimate bag of tricks).

What better mascot, then, for the insidious possession of children via smartphones than a seemingly harmless but strangely unnerving clown-woman like Gladys, whose high-end accessories chime with the shiny, hyper-consumerist forces of Big Tech but who, on closer inspection, reveals more ominous qualities?

Popular social media platforms and online forum sites like Reddit and 4chan offer an exciting, self-perpetuating abyss of entertainment very often in the form of fake news, radicalising content and AI-generated material ranging from brainrotting “slop” to deeply harmful material. This is to say nothing of how such spaces help springboard the creation and dissemination of mass-shooter content, bridging the gap between murderous fledgling fantasies and acting upon them.

Indeed, the vast, mercurial world smartphones open up for young people today is one that is little understood and commonly ignored by parents, as Netflix’s blindsiding drama Adolescence demonstrated this earlier year. Here once again, the lyrics of Harrison’s ballad resonate. Written in essence to caution against the forces that seek to influence us, he urges us to beware “The pain that often mingles / In your fingertips.” Whether smartphones or semiautomatic rifles capable of taking the lives of, say, 17 school pupils, what are the grown-ups helping place at the “fingertips” of young people?

Always on, always within reach, such corners of the internet are fertile grounds for manipulating febrile young minds and perhaps fill a thrill-seeking recreational void once occupied by fairgrounds and amusement parks. Hence the carnivalesque quality of the Holladay brothers’ richly textured OST, whose enthralling, hypnotic melodies seamlessly evoke the sensation of going under, of falling prey to a mystic force like Gladys (or the depths of an Instagram rabbit hole).

If only Weapons had the capacity to delve further under the skin of this issue. However, having circled the narrative cursor so far outward from those centrally implicated in the disappearance — entering the worlds of cop Paul, addict James and principal Miller, etc. — we wind up so far removed from the film’s core premise that any meaningful commentary on the mass-hypnosis of today’s youth is smothered by its own form.

Crucially, what made Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead a classic is the way that its alternate perspectives orbited around one specific event — the Hanson brothers’ robbery of their parents’ jewellery store. The convoluted non-linearity of Weapons, however — while brilliantly executed — jars with the diffuse and ongoing mystery of its own premise. The result? A restless, ephemeral format incapable of accommodating the contourless premise of a mystery spanning months and implicating scores, if not hundreds of people. Cregger’s origami crane of a plot structure might be nice to look at, but it has no legs to stand on.

Despite technically bringing everything together — and enjoyably so, it must be said — Weapons fails conclude the mystery in a way that is worthy of Cregger’s talents, or that its auspicious opening sequence promised. Lamentably, we’re lumped with a rather redundant and strangely abrupt ending in which Garner and Brolin end up virtually irrelevant — not just because they’re buried by the film’s secondary characters but because they’re drastically upstaged by the lesser-known actors who portray them.

But I’m here for Weapons, thanks mostly to the immersive work of cinematographer Larkin Seiple and some of this year’s boldest performances (needless to say, Cregger has landed Madigan the career revival of a lifetime through the evil witch-turned-gay icon that is Gladys). Through what is an original and needle-moving film, Cregger throws much needed light on society’s knee-jerk compulsion to place blame on anyone but themselves and their own subconscious beliefs. As we perennially take aim at teachers other professionals like them whose job it is in fact to keep our young safe, Weapons stops us in our tracks to ask: who’s the real witch here?

With some tighter, more integral storytelling — along with the increased consistency this affords — Cregger, it’s fair to say, is en route to creating something truly groundbreaking in the horror world. This, however, isn’t quite it.

This article was first published on Counter Arts on August 31, 2025

Leave a comment