In this terrestrial memoir, Masud excavates the land beneath us to reveal the spatial politics within. In doing so, she exposes the neocolonial endeavours of world leaders today

Archaeologist Francis Pryor writes of the Fens, south-east England, that “if any landscape can provide darkness, with a very real hint of menace, it is most surely the Fens.” Fen aficionado and poet Edward Storey, meanwhile, writes of the precarious wetlands that inspired his work, that, “You walk the roof of the world here. / Only the clouds are higher and they are not permanent . . . Here, you must walk with yourself, / Or share the spirits of forgotten ages.” Storey’s words hauntingly capture the vertiginous, vast claustrophobia we find in such flat spaces, their end-of-the-world quality forcing visitors to invent or see things that aren’t there — the “spirits of forgotten ages” or the invisible “menace” evoked by Pryor.

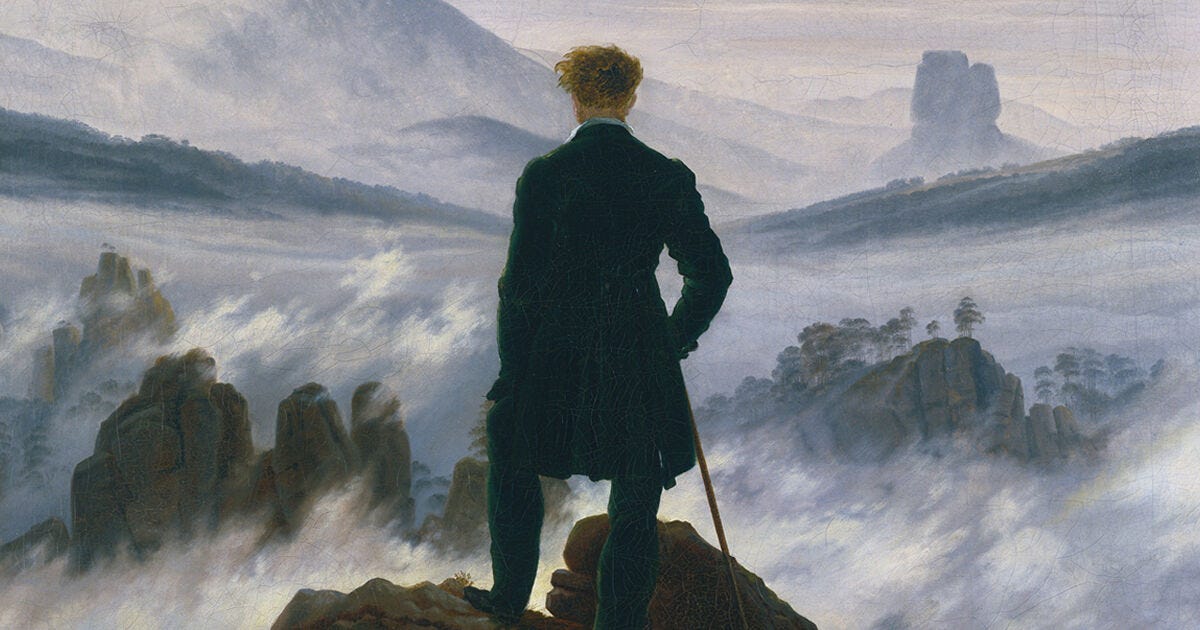

Indeed, vast, open flat spaces — as English scholar Noreen Masud demonstrates in her topo-autobiographical memoir A Flat Place — pique a very human fear of emptiness. “Flat landscapes,” she writes, “ask us to not tolerate knowing things.” Hence our industrialising need as humans to fill unfurling, empty lands like the Fens with hyperbolic superstition in lieu of something else — a narrative of some variety to help situate the slippery lands, to reify something deemed lacking. She cites the swirling, mercurial landscape depicted in Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) — perhaps the most definitive representation of nature in the Romantic canon — as a testament to this: bursting with pastoral grandeur, the landscape seems almost to move, to do something, and couldn’t be further from anything described as “flat”. The painting resists nothingness and celebrates the drama of somethingness, of preexisting narrative.

However, unusually flat, otherworldly spaces for Masud are unique in their ability to starkly reveal this proclivity to fill empty space by exposing the way in which competing forces seek to occupy them. Specifically, their naturally level terrain exposes our efforts to control and determine the land both physically and symbolically through violence and myth.

The Fens, for instance, are a slippery region of no-man’s-land between the forces of nature — the sea — and mankind — the agro-industrial efforts to harness, control and inhabit the land through centuries of drainage, pumping and agricultural exploitation (in addition to being the subject of much myth-making). Plural and vast, the Fens are divided into multiple sections of land, drawn up and labelled as though in an apparent bid to control them. And yet the land ever seems to evade our control.

Crucially, Friedrich’s pinnacled masterpiece of 1818 frames the natural world as one of two defining ways of thinking about man’s relation to nature. The first posits nature as a muse, a source of sublime inspiration to be left — like Friedrich’s landscape — untouched, untainted by man. The second argues that the natural world is something to be tamed, harnessed and mastered in the name of human progress.

This latter dichotomy — man versus the optimizable natural world — finds its origins in the historical division between culture (that is, the “noble” pursuits of man) and nature. Natural space has, since the Scientific Revolution, served as an infinite source of material exploitation, something to be studied, optimised and franchised in the name of man’s betterment. (Even Friedrich’s cocksure hero, situated in the painting’s dead centre, appears to stand above and to conquer the landscape before him). Scientist Francis Bacon thus argued that nature ought to be “conquered by obedience,” and that “culture” — in its many expressions — marks a triumph over nature.

Bacon’s utilitarian culture/nature divide, Masud highlights, heads up a long list of empiricist binaries that divide much of the world into competing camps, such as man/nature, nature/nurture, real/artificial — divisions that have come to define our anthropocentric way of viewing the world. This doctrine of Nature-as-a-tool — as something to be subjugated and used — neatly aligned with the mercantilist pursuits of Bacon’s Europe in the so-called Age of Discovery, during which seafaring voyagers deemed the territories they encountered on their travels as inferior and “uncivilised” land to be tamed and exploited. Moreover, the colonial links they established would eventually help pave the way for capitalism’s eventual rise as the dominant economic system — one interconnected through global trade routes predicated on dominant/submissive oppositions like rich/poor, Western/non-Western, civilised/uncivilised that remain in place to this day.

In the eyes of white venturers of Discovery Europe, the “rest” of the world (that is, a non-white world) was viewed as attainable, economically fertile land by virtue of its otherness, land to be occupied and exploited. Hence, centuries later, at the height of European colonial fervour, the concept of manifest destiny — the nineteenth-century belief that American settlers were, through divine right, placed on the land to spread Protestant ideals and culture westwards. No clearer is this shown than in the large-scale deforestation of the Amazon rainforest in the twentieth century onwards, whose ecocidal monopolisation (predominantly in the service of the international beef and beef trade) is perhaps the most disturbing manifestation of the flattening forces of colonial-derived capitalism.

And yet, how to occupy and fill a space whose very essence is its flatness, a quality which inevitably accords the landscape an element of danger? Naturally flat terrains — places like boggy marshes, perilous coasts and arid deserts — are geographically inhospitable due to the increased flood risk, susceptibility to soil erosion and potential for wind erosion they carry, making them vulnerable to natural disasters and posing challenges for human settlements and agriculture. How to flatten, in other words, land that is so obstinately flat, land that resists occupation?

Unlike Friedrich’s epic painting, flat, often peripheral places resist somethingness on account of their unique terrain that refuses to be optimised. A thorn in the side of the seemingly limitless endeavours of the white man, they problematise this notion of productivity at all costs through their defiance, their ability to refuse the industrialising forces of man — deforestation, urbanisation and agriculture — that stretch to blight any patch of the earth it possibly can.

The Fens are just one of a handful of British landmarks to feature in Masud’s memoir that possess a certain flatness she yearns for — an idyllic emptiness found elsewhere at Morecambe Bay in the north west, Orford Ness in the south east and the low-lying areas of Orkney Islands west of Mainland in Northern Scotland.

Born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan, Masud begins her book by recounting the tantalizingly level landscape that first brandished her mind and shaped her research ever since — namely, the “perfectly, shimmeringly flat” fields she grew up seeing in the city’s outer limits en route to school. Glimpsed gleefully from the cramped backseat of her aunt’s car (which she shared with her three bickering sisters), these open fields offered Masud’s child-self a near-fantastical balm to the confinement of her childhood — and, specifically, the clutches of her abusive father.

We’re afforded only carefully selected insights into Masud’s youth, but enough to gauge that her Pakistani father — a severe man and respected doctor whom she describes as “half-god” — abused Masud, her mother and three sisters (whom she refers to by pet names for anonymity). Barricading them in the home by fencing the windows with bars and chicken wire — through which Masud recalls gazing at the children playing and people going about their day — Masud’s father manned a home that was by all accounts a prison. There was “no talking to neighbours. No inviting classmates or friends round to the house,” she writes. Enrolling Masud and his sisters at a strictly English-speaking school, her father prevented them from fully learning and speaking Urdu and Punjabi with family members.

An antithesis to the claustrophobia of her childhood, Lahore’s “huge empty fields” became a powerful metaphor — a foundation — for Masud’s life. Quoting Virginia Woolf’s autobiography, she thus writes: “If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one fills and fills and fills — then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory . . . of hearing the waves breaking [in St. Ives].” Where for Woolf, life is carried along by the memory of waves, for Masud it is the “green misted fields” of her youth.

And yet, they are more than just a foundation for her existence. The flatness of Lahore’s rolling fields in fact becomes a metaphor for Masud’s entire existence. Her body, she highlights, which, like the ground, she describes as “hard stone,” longs to lay flush with the flattest landscape she can find even as an adult. “I love flat landscapes,” she writes, because “they won’t compromise. They are stiff and still, like me.” The “knots and gnarls” that speckle the fields of Lahore — and dash the flat stone flooring of her home she would lay down and caress fondly as a child, an adjunct to the unfurling fields — mimic the “knots and gnarls” of her life.

Indeed, like such spaces, Masud herself operates as a stubborn, quietly unyielding entity — hence her lifelong affinity with such landscapes. Against the will of her father, she writes that she furtively took a GCSE and A-level in English literature, eventually enrolling to Cambridge to study the subject and pursuing an academic career years later. This, she speaks of almost as an inevitability, something encoded into her body — a natural force of resistance like the features of the immutably flat landscapes she covets. Despite the forces that seek to define and control her identity — to superimpose attributes and qualities onto her — Masud doesn’t compromise. True to character, Masud warns early on that we are not to expect a story of hope, which Masud shuns as an idealised Western construct she can neither offer nor yield to; much like herself, A Flat Place is defiantly flat.

A Flat Place chronicles Masud’s journey across Britain, with each of its chapters comprising a separate British landmark. Roving the land, Masud appeals not only to her life-long fascination with such spaces, but their affinity with her own trauma — revealing to us, in the process, the layers of trauma and conflict endured by the land. Just as one might amass a collection of stones and debris harvested from the beach, Masud slowly amasses the pieces of her fractured identity, bringing her closer to understanding both her childhood trauma and her place in the world as a British-Pakistani woman.

As Masud makes plain in the book’s introduction, her personal trauma lies at the heart of A Flat Place. It is unpicked and understood through sessions with her therapist, presented in the memoir in snippets of conversations which — like the excerpts of topographical poetry Masud peppers throughout — guide and ground Masud like a ship to a lighthouse.

Specifically, as Masud’s therapist helps her to see, Masud suffers from complex post-traumatic stress disorder, or c-PTSD. Trauma that cannot be attributed to one specific event, c-PTSD manifests more as an existence, a looming anxiety that inhabits the periphery of certain lives like a tide threatening to engulf the land. It exists as a “continuing background noise,” as she writes, citing feminist scholar Laura Brown — a quiet hum that follows the “lives of girls and women of all colors, men of color . . ., lesbian and gay people, people in poverty and people with disabilities.”

It’s through this “continuing background noise” that Masud channels the frequencies and wavelengths found beneath the surface of a space’s celebrated history — more often than not the heroic and patriotic narratives of Anglo-military forces and industrial power, the myths and dreams around which the national image is constructed and maintained — to penetrate the palimpsest of the land beneath us. Listening to land, Masud asks: What’s in a place, beyond what the eye can see (or, indeed, what we’re told to see)? Who can be said to lay claim to land, and why? What forces are at play in the struggle to lay claim to and exploit the land beneath our feet?

Despite their appearance of nothingness (and considered irrelevant to most beyond their suitability for walks with panoramic views), the flat places Masud visits are, in fact, rich with history and conflict — with what she calls the “imperceptible distress in the landscape” detectable only to the trained ear. This, she finds just about everywhere, humming in the scenes of everyday existence. As she writes on life in the UK, where she moved aged sixteen with her mother and sisters: “I can’t quite trust in the clean water that flows from the tap; the full supermarket shelves; the orderly parks and gardens. I feel as though it’s built on a lie, on hidden or delegated sufferings.”

Masud is quickly able to detect such lies a country will uphold in the name of maintaining a particular national identity. No clearer is this, perhaps, than in the UK, where efforts to perpetuate a living, proud and dominant British identity are part of the country’s DNA. This, Masud captures with incisive, irreverent analysis. En route to Welney, for instance, during the first leg of her journey visiting the flattened Fens, Masud spots bright red telephone boxes dotting the gardens she passes, often accompanied by Union Jacks, tractors and ceramic dogs.

To the proud, myth-making British, the telephone boxes — and their accompanying totems — are quaint but powerful symbols of a coherent, unified nation.

To Masud, however, such paraphernalia are but transparent props, garish “tat” symptomatic of a desperate need for national identity as blatant as the moniker used to christen the public walk she journeys towards: Hereward’s Way. Named after the much mythologised English nobleman said to have fought and rallied against the Normans in the eleventh century — readily served up as an icon of “true” Britishness and defender through to the late Victorian age — the walk is demonstrative of the UK’s reluctance to (fully) part ways with chivalric, white notions of a British collective.

And yet not all of the sites Masud visits are considered geographically inhospitable. Visiting Newcastle Moor — an unusually large, contested stretch of “common land” lying crudely close to the city centre — Masud probes the perfectly habitable landmark to gauge the many competing narratives beneath. Each occupation of the land (a mixture of both flat and hilly grassland) since the eleventh century effaces, or “flattens,” the next: it served as a smallpox hospital in 1882, razed in 1958; a prisoner-of-war camp for Italian POWs during the 1940s, demolished a decade or so later; and mining territory from the medieval period through to the twentieth century. Today, the land is used as the site for Europe’s largest fairground, the Hoppings.

Anomalously, the Moor is still owned in part by the Freemen and is therefore shielded from total control, with farmers being permitted to graze their cows to this day. The stretch of land is a contested, mercurial space that is ostensibly habitable owing to its mainland situation, but which, in its limbo state, remains a site for troubling nothingness. It is perfectly habitable, marketable and profitable land, left largely uncapitalised. In 2003 an architect declared Newcastle Moor the largest missed opportunity for development in the UK.

However, it’s the flat spaces found at the country’s periphery which Masud dedicates the bulk of her memoir to — and which can offer us vital reflections of neglected or concealed racial histories. Visiting Orford Ness, for example — the outlandish, apocalyptic shingle spit reachable only by boat — Masud considers the narratives she is expected to learn and appreciate while there.

As well as being an important nature reserve, Orford Ness is primarily known for being the former site of secret British military testing throughout World Wars I and II and subsequently the Cold War. Its association with the very masculine subject of war, Masud highlights, makes Orford Ness instantly “legible” to a public fed on binary, simplistic narratives of opposition: “In war, there’s tension, two opposing sides . . . Violence and conquest.” Like colonialism, war is a story of dominance and submission. Exploring the landmark on a tour group, Masud quickly senses that she’s seeing the location through “too many pairs of eyes” as someone might suddenly sense they’re aboard the wrong train.

“War and whiteness organize the world,” Masud submits, which together cast a shadow over almost anything it can reach. Naturally averse to this gaze, Masud seeks out the scars and blemishes of the parts little acknowledged by visitors. Aboard a tour boat sailing down the River Ore, a large, picturesque river that divides mainland England and the spit, they pass the Chinese Wall. It’s a feature glazed by the tour guide with as much ease as it was in history. Built by a Chinese labour battalion in the First World War, the seawall is a testimony to the silent role of the Chinese labourers in supporting the British during the war (and once again in the Second). Yet, because the wall fails to adhere to the white, chivalric narrative of the allied powers in both wars, the wall is routinely forgotten — one of many ways the West continues to render the 140,000 to 320,000 Chinese men who contributed to the war all but invisible.

Similarly, at the vast, incandescent Morecambe bay, north-west England, Masud studies the signage studding the periphery of the boggish terrain and warning visitors of quicksand — the land’s “EXTREME DANGER.” Dangerous for whom, exactly? asks Masud. In 2004, she highlights, Chinese workers were smuggled into Britain to pick cockles along the Morecambe coast. When the tide came in and the untrained workers didn’t know what to do, 21 of them drowned. The tragedy resulted in one Chinese man being sentenced, while the two English men that agreed to pay the workers £5 for every 25kg of cockles they foraged were let off.

This is the world viewed through the lens of a female British-Pakistani, someone with a visceral and personal understanding of the dominant role whiteness plays in global spatial politics. And, as she relays her experiences travelling the UK, Masud often brings us back to the tensions between imperial Britain and the Indian subcontinent — a geopolitical rapport that looms large over her memoir.

Masud succinctly maps out the history of the region following the end of the British Raj. Attempting to assuage the internal troubles it helped exacerbate through its policy of divide and rule, the UK hastily ceded control of India in 1947 following its decision to divide the country into Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India. This, as Masud highlights, was a reconfiguration drawn up “roughly and incompetently” by a British lawyer “who’d never visited the [Indian] subcontinent.” Post-division, the region was plunged into a prolonged series of violent internal struggles and identity crises, including the deaths of one million and the displacement of over 12 million people. Still often thought of as a simple solution to a simple problem, India’s partition in reality set in motion a perilous process of creating its own image in the wake of upheaval.

It certainly must have felt like a simple solution to the world’s largest empire, for whom land beyond British soil was a literal map — flat, controllable territory governed by the lines it drew at whim.

Indeed, Britain’s handling of India’s partition ignores — and therefore cancels — the complex, lived identities of the communities that inhabited the subcontinent prior to British involvement. What did it mean to be “Pakistani,” separated from both India and the British Empire, Masud questions? Was Pakistan the home for Indian Muslims only? The spiritual home for all Muslims? And, in Masud’s case, what did it mean to be of both British and Pakistani descent, with a mother from the former coloniser and a father from the country it effectively created with the hurried stroke of a pen?

Masud’s identity as a Pakistani-British woman caught in the ambiguous space of postcolonialism remains integral to both her identity and A Flat Place. On the one hand, through her English schooling in Pakistan Masud was forced to absorb a rose-tinted image of England (snowball fights and crisp brown leaves), and rather symbolically made to write the line “English is my favourite subject” as part of her rote learning. On the other hand, she had to learn what Pakistan must have been like according to white Britons upon relocating to her mother’s native country, where, resorting to images of “burkas and terrorism,” they assume her domesticated entrapment in Lahore to be typical of Pakistan, even “normal.”

Yet, as she stresses, Masud’s childhood was unusual by both British and Pakistani standards (the latter tolerates both the oppression and the success of women, she highlights). Rather, much of Masud’s suffering can be viewed as being resulting from the space where both Britain and Pakistan collide, or overlap, as forces.

Crucially, this is an imbrication found embodied in the Westernisation of her father, an “impatient, fitful” but highly respected doctor whose presence, like the shadow of colonial Britain, quietly stalks the pages of this memoir.

And as with the history of British-Indian relations, Masud dedicates a substantial amount of time throughout the early chapters to focus on her father, honing in specifically on his obsessive but revered work ethic. This she implicitly attributes to his nature as a staunch “anglophile” who detested Pakistani culture — his suave “Western suits” and aggressive work ethic being symbols of his allegiance to the revered British and American hustle culture.

A British-colonial import of the nineteenth century, her father’s fixation with achievement betrays a certain superiority complex, a need to deflect feelings of non-Western inferiority through excessive productivity. Eschewing Allah, he proudly professed instead to worship Apollo — his personal god of choice Western Greek mythology — who, commonly pitted against the god of chaos and lust (Dionysus) is associated with the rational and self-disciplined aspects of human nature. Tellingly, as well as being “half-god,” Masud describes her father as “half-underdog” — a dualism that embodies his nature as both a mascot for Western culture despite originating from a former British colony.

Symptomatic of this complex is what Masud refers to as his god-like “optimisation” of herself and her sisters — both as girls (not boys) and British-Pakistanis (not white). Women’s bodies, especially those that are ethnic-minority, are projected onto, defined and optimised even by men of colour, planted upon as though fertile stretches of land to be tamed, shaped and exploited. As she writes, “[m]y father put his two big hands on the ground around us, and we crawled around inside.”

Nature is widely mythologised as female, while civilization — culture, education, arts, productivity — is thought of a masculine, the preserve of men. Francis Bacon, to revisit the revolutionary scientist, symbolically wrote of the natural world in Novum Organum (1620) that, “I come in very truth leading to you Nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave.” Blurring the distinctions between land — “Nature” — and people — “her children” — Bacon melds femininity and foreignness into a coherent, unified other.

Indeed, bound up within this gendered othering is a strong (and eroticised) ethnic component that positions the white European man as superior to the feminised, non-white foreigner of the exoticised “New World.” This is echoed in accounts from mercantilist-colonial exploits of European scientists and expeditioners from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries onward. Voyager Christopher Columbus’ declared in 1498 that the world was not round, but a breast, with the recently discovered South America forming its nipple. Meanwhile, as English scholar Revathi Krishnaswamy highlights, explorers visiting eighteenth-century India documented the supposed “femininity” of the people and customs they encountered there — including its men who, lacking the “chivalric ideal of manhood” embodied in the Englishman, were deemed “weak and ineffectual.”

Conflating the country’s effeminateness with economically fertile land in need of “civilizing,” the British saw it as their duty to masculinise and, ultimately, subjugate India. Unsurprisingly, then, at the heart of her father’s optimization of Masud and her sisters were efforts to masculinise them. Thus, choosing not to wallow in the “tragedy” that he hadn’t fathered sons, he rewrote the gender of his children by referring to them as his “boys,” cutting their hair short and expecting from them respected and lucrative careers typically associated with (Western) men. For her father, as for the Western gaze, Masud and her sisters formed part of a malleable Other, a blank, flat canvas onto which their professional and gender identities were to be written — all in the name of being civilised.

In the process, the bodies of Masud and her sisters become objects, tools — instruments that serve to reinforce her father’s own troubled self-image and foster a sense of “civilisation” he perhaps feared lacking in himself. As she recounts, her father subjected them to military-esque quizzes on impossibly abstract topics — guessing which pillow belonged to which sibling through smell, for instance — exercises they were made to perform in total stillness to avoid being hit. She recalls even once being used as an international mule (to transport what, exactly, she still does not know).

More disturbing still, Masud and her sisters posed as living cadavers for their father’s medical experiments through the mysterious “vials and needles” he routinely brought home and used on them and the “heaps of tablets” he had them wash down at breakfast and dinner. Masud elaborates that “[i]t was all part of competing with the imaginary boys” they were expected to hold up against.

Masud brings the reality of this medical abuse home powerfully when she writes bluntly, concluding a lengthy passage on her father’s work-from-home compulsions: “My father practiced on us.” Crucially, her words are an eerie repetition of the same line found only a few passages prior in which she refers to father’s preference of “practis[ing]” his English “on” them. Linking the white patriarchal anglicisation of subjugated countries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the physical exploitation of its native peoples, her father’s (seemingly non-therapeutic) procedures echoe accounts of vaccination trials carried out on French and British-owned slaves in the Caribbean in the eighteenth century, widespread human experimentation on nineteenth-century slaves in the southern states of America and on unwitting African American subjects that persisted well into the twentieth.

Masud’s heavily policed childhood was, in other words, one quite literally confined to the godly hands of a man. It was, as she aptly puts it, a life lived at the mercy of a man “doing what he thought best and never asking for permission in the way what men are allowed to do all over the world.”

Our current geo-political climate is dominated by such men — narcissists with blatant superiority complexes bent on bolstering their self-image through neocolonial posturing (or, indeed, all out war). Foreign land, in their view, is considered flat, fair game, ever attainable in a fight to look bigger in an increasingly multipolar world. As Putin stretches his ego across Eastern Europe, for instance, second-term US president Donald Trump similarly casts his neocolonial gaze across Canada, Greenland and anywhere his administration can sink his teeth into. (Though the latter was referring to the colonisation of space when he referenced the nineteenth-century concept of manifest destiny in his inauguration speech, his words bring new meaning to the expression “the sky’s your limit” in terms of colonial expansion).

Moreover, even if the publication of A Flat Place predates events following October 2023, Israel’s ongoing occupation of Palestine chimes closely with Masud’s study of power and land in fascinating ways.

Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current war on Gaza is a brutal advancement of the country’s historic occupation of the region — one closely bound up with Israel’s Westernised, neoliberal economy. Donald Trump’s Netanyahu-approved dreams of franchising the Gaza strip — creaming off Israel’s literal flattening of Gaza by converting the area into a profit-churning “Middle Eastern Riviera” — are a stark reminder of this. Prior to Trump’s deranged brand of neocolonialism, however, the dollar signs were there. Israel’s real estate venture into territories of the West Bank, for instance, signals that recent profitising of Palestinian misery is part and parcel of his genocidal policies. Luxury rentals listed on AirBnb and Booking.com in illegal settlements in the West Bank have begun cropping up, many of which boast views of “untouched” land which in fact belongs to Palestinian locals, suggesting a civilisational flattening of people, land and culture in the name of profit.

Others reaping the benefits of Palestine’s flattening are tech and manufacturing giants, whose services and products are purchased by Israel as instruments in their chokehold of Gaza and the West Bank. This includes household names like Google, AI software engineer Palantir, construction manufacturer Caterpillar, vehicle maker Ford and weapons manufacturer Colt — who, known for supplying Israeli settlers of the West Bank its arms, was dubbed by a Virginia tech professor in 2020 as “a technology of Manifest Destiny.” In our globalised era of shadowy tech, neocolonialism is a seemingly limitless contagion buffeted by the winds of investment — facilitated by the remote capabilities of data mining and artificial intelligence Palantir and Google respectively provide Israel from afar.

And yet, on a more psychological level, the Israeli prime minister can be said to share key characteristics with Masud’s oppressive father. The pair are certainly united in their respective campaigns, with Netanyahu’s ongoing colonisation of Palestinians mimicking the literal imprisonment of Masud and her family at the hands of her “megalomaniac” father — while both are spurred on by a toxic subservience to Western culture and an internalised repudiation of Eastern civilization.

Indeed, through his self-prophesied position as a buffer between the West and East, Netanyahu operates at the intersection between the West and “uncivilized” Arab nations — downplaying his proximity to what he deems as an inferior race by pledging an allegiance to America in a way that echoes the violently westernising compulsions of Masud’s Pakistani father. Simultaneously residing at the helm of a viciously neocolonial government while belonging to a minority people with a profoundly traumatic past (one savilly exploited by the Nikud party in October 2024 to commemorate the one year anniversary of Hamas’ attack), Netanyahu might best be branded with Masud’s own description of her father: half-underdog, half-god.

Moreover, where the Israeli prime minister is recognised as a “bright,” “organized,” “strong” and “powerful” high-achiever but known as “narcissistic, entitled and paranoid” to some and egocentric, belligerent and untrustworthy to others, Masud’s father is at once a “genius and maverick” yet “rude,” “impatient, fitful and indifferent to rules.”

Like the Westernisation of Masud’s father, much of this might be the corollary of Netanyahu’s undeniable Americanisation which, despite his insistence on Israel as his home, reveals a deeply rooted admiration for US cultural hegemony. He possesses a prestigious “double-loaded” Ivy League education and boasts an early career in finance with the elite American consulting firm Boston Consulting Group before becoming Israeli ambassador to the UN in the 1980s (during which time he befriended the father of Donald Trump). Most tellingly, Netanyahu anglicized his name to “Ben Nitai” so that, while living there, Americans were able to pronounce his name — adding to the testimony of Netanyahu’s once close friend, Ariel Barzilay, who, describing Netanyahu’s sojourn in the US (where it’s alleged he would have remained long-term were it not for the death of his brother), labelled him as “completely Americano.”

Like man, like country. In the 1980s — despite the country’s efforts to solidify Israel as the Jewish homeland through nationalist measures like archaeological digs proving Jews laid claim to the land before the Palestinians — Israel adopted a staunchly “American-style” economy. This culminated in the Reagan-led Economic Stabilization Plan of 1985, an economic restructuring that quickly ushered Israel into the global economy — in turn enabling Israel to become the important technological and economic ally on the world stage as (a “normalized” Western state) it is today.

This paints the complex image of both a man and a mythologised idea of a nation between worlds, aligning with Netanyahu biographer Anshel Pfeffer’s celebrated book which calls the nation of Israel a “hybrid of ancient phobia and high-tech hope; of tribalism and globalism — just like [Netanyahu] himself.” Victims of this tension between tribalism and globalism, Palestinian civilians become non-beings, ghosts, shadows of the West. This, of course, is part of the dehumanising ideology of Israel’s campaign, which the shocking reports of weapons testing carried out on Palistinians by Israel — the world’s largest exporter of drones — further attest.

Opening chapter five of her memoir, Masud borrows from Judith Butler’s Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? with the following quotation: “[S]pecific lives cannot be apprehended as injured or lost if they are not first apprehended as living.” In other words, to truly acknowledge the loss of humans, they must first be thought of as human beings.

Butler’s words powerfully echo Masud’s very own when she writes on the post colonial experience that to grow up in the shadow of an occupier is to exist as a “defective shadow of the West”, or that the “white children” she grew up forced to learn of English school “were human” while “we [her sisters and fellow classmates] were ghosts.”

Who do we consider worthy of the epithet human, and not? Reading A Flat Place, I’m reminded of journalist Naomi Klein’s invocation of what she calls the “shadowland,” the near-invisible countries of the so-called “global south.” These are the “developing” nations across Africa, Central and Southern America and South East Asia that prop up and support the Western world through cheap outsourced labour — stitching our clothes, mining the batteries of our cellphones and moderating the disturbing content they put out into the world. Existing on the periphery of capitalist society, and yet integral to it, these shadow places are unacknowledged beyond their status as natural disaster zones and occasional offering as “exoticised” countries of wonder available to the Western traveller.

Again, this is the “hidden or delegated sufferings” Masud finds hidden in everyday British life, vibrating in the abundantly stocked shelves of British supermarkets. It would take a global pandemic to expose the globalised world’s balance of colonial power, the structures built upon “delegated sufferings” — a time when, as Covid-19 engulfed the world in 2020, the supermarket shelves were tellingly stripped bare.

Forcing Western nations to exist in a state of imprisonment, Masud asserts, the pandemic pushed the “global north” into a lifestyle widely endured by the countries it continues to rely on for its day-to-day functioning — very often a curtailed, limited and subjugated life. While countries like the UK and the US begrudgingly adapted to this “new normal,” for Masud the lockdown era of 2020 and 2021 was a normalisation of her normal. As countries flocked to “flatten the curve” and live somewhat flattened, Masud writes that she was, conversely, free, able to live yet more flatly.

During the pandemic, the world was, in many ways, forced into a level playing field, its order flattened. The people that helped keep the world turning — nurses, bus drivers, shop workers, refuse collectors, carers, hospitality staff, Amazon and other fulfillment workers — were for a brief period lionized, valued suddenly for their role as the backbone of society. Is it a coincidence that a large proportion of the people who make up these jobs are ethnic minorities and immigrants, originating as they do from countries the West views as less than, as shadows of themselves carrying out work the shadow work they deem as beneath them — people who, in the UK, Labour leader Keir Starmer has further pledged to demonise through recent anti-immigrant rhetoric?

The people of Palestine to this day continue to exist in the long, claustrophobic shadow of war, to live imprisoned within the hands of man, victims of a war widely thought to disproportionately affect women. As they do, the near-ceaseless sounds of war form the “continuing background noise” of trauma that is the soundtrack to everyday Gazan life, so much so that when the high-pitched whizz of the drones high above — dubbed the “zanzana” by Palestinians — is halted briefly, the silence is instantly noticeable.

The whir of the Western-made drones is the sound of man-made injustice, a reminder that Palestinians inhabit lands flattened by the whims and caprices of a megalomaniac leader. Once again, Edward Storey’s apocalyptic eulogy to the Fens comes to mind. Describing the distant reeds of land as the “final barrier,” the “Houses and farms [that] cling like crustaceans / To the black hull of the earth,” his words are an eerie doubling of Palestine’s destruction — land sheared to a deadly, charred husk by the flattening engines of neocolonialism. In the apocalyptic, flattened landscape of Gaza, who will hear the cries of genocide’s ghosts?

This article was first published on Counter Arts on May 15, 2025

Leave a comment