For generations robbed of a stable future, “Buffy” feels written for our hellish times — complicated, however, by the show’s behind-the-scenes reality

The premiere episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s pivotal third season, “Anne,” is symbolic to say the least. In it, we follow “chosen one” slayer Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) attempt to lead a civilian life under the alias Anne (her middle name), having left Sunnydale after the bulk trauma of being expelled from Sunnydale High, kicked out of her home by mother Joyce (Kristine Sutherland), and being forced to kill vampire-boyfriend-turned-post-coital-monster Angel (David Boreanaz). Incognito, she waits tables in an especially seedy Los Angeles. There, few acknowledge Buffy/Anne except the kind, compassionate Ken (Carlos Jacott), who hands out flyers offering to support the young “lost souls” of LA.

Things change when she bumps into the rough-living Lily (Julia Lee), who we knew as the outcast wannabe-vampire Chanterelle from season two. When Lily’s boyfriend Ricky turns up dead and somehow vastly aged, Buffy finds herself unable to ignore the signs of evil at work. Forced to dig, she learns that LA’s outcasts are being catfished into working for a subterranean industry of human slave workers — headed up by none other than friendly-shoulder Ken.

A despotic demon disguised in a layer of human skin, Ken harvests the young and vulnerable from the streets, forcing them — like Ricky — to toil for the rest of their life and identify as “no one.” On entering the scheme, in fact, if prisoners fail to identify as such when asked “Who are you?” by a club-wielding demon guard, they’re bludgeoned and killed.

Finding herself in the jaws of the scheme, Buffy is asked this very question. Faced with a choice, she can officially become “no one,” the shadow of herself she came to LA to be; or relinquish Anne and become her true self again — the slayer.

Brazenly reclaiming her identity, Buffy delivers one of the show’s most memorable morsels of whip-smart sarcasm. Looking up to meet the guard squarely in the eyes, she pluckily states: “I’m Buffy, the vampire slayer. And you are?”. All hell breaks loose, and a back-to-form Buffy slays her way through the demonic factory, and with the help of Lily shuts the scheme down. Leaving her apartment to Lily, she moves back to Sunnydale and rekindles with Joyce, with whose help she wrangles her way back into Sunnydale High for her final year.

Buffy’s senior year won’t be any walk in the park, however. “Anne’s” commentary on capitalist exploitation sets the theme for season as a whole: to be a young adult — and, in particular, outside of the “norm” — is to exist in a duplicitous, phallocentric world that will strip you of your powers and leave you helpless (hence the plethora of distinctly brutal male villains that permeate season three’s episodes).

Indeed, breaking away from the more inward, close-knit storylines of seasons one and two (that covered friendship, romance, sex), Buffy’s third season marks a foray into the political to explore life beyond the comfortable confines of adolescence and the failures of the social contract beyond it.

· · ·

And when, in the real world, has the social contract ever seemed so broken in recent history?

Despite its unserious presentation, Buffy is lauded for its shrewd sociopolitical and feminist commentary, maintaining an impressive balancing act between frivolous forays into high school politics and complex explorations of cultural issues like addiction, misogyny and, chief among them perhaps, the abuse of power.

Sunnydale’s “dark forces”—emanating from the “Hellmouth,” a concentrated hot-spot of evil the town sits upon — are widely considered a metaphor for real-world corporate greed and exploitation, a parallel made clear in the show by the role humans play in maintaining or joining forces with demonic powers.

Indeed, the divide between good and evil, human and non-human in Buffy isn’t cut and dry. It’s an unspoken truth amongst the town’s citizens that evil forces exist, but are shrugged off as “what goes bump in the night” much in the same way that deleterious effects of corporate greed in the real world are despondently acknowledged but accepted as the norm.

This is a “norm” perpetuated by conspiratorial, power-hungry (human) officials across Sunnydale’s public institutions — its local government, schools, police and militia forces. In league with dark forces, they help maintain the status quo by pitting younger generations — “troublemakers” — against society’s elders and framing them as the cause of life’s woes. (As if to spotlight this, the entrance to the Hellmouth sits directly beneath the high school library in a pointed reminder of this).

Buffy’s fight is in many ways a feminist rebuttal against the destructive, patriarchal capitalist forces that view marginalised identities — and their inherent power — as an obstacle, played out in the perennial battle between young and old we’re all too familiar with today.

This is a tension is already put into motion by both Joyce’s and Sunnydale High’s expulsion of Buffy in season two’s finale, both rejections of Buffy’s queer-coded role as slayer. The episode “Gingerbread,” for instance, draws on a popular fairy tale to explore the inherent distrust between the young/old, parent/child dichotomies in ways that eerily echo today’s fraught socio-political climate.

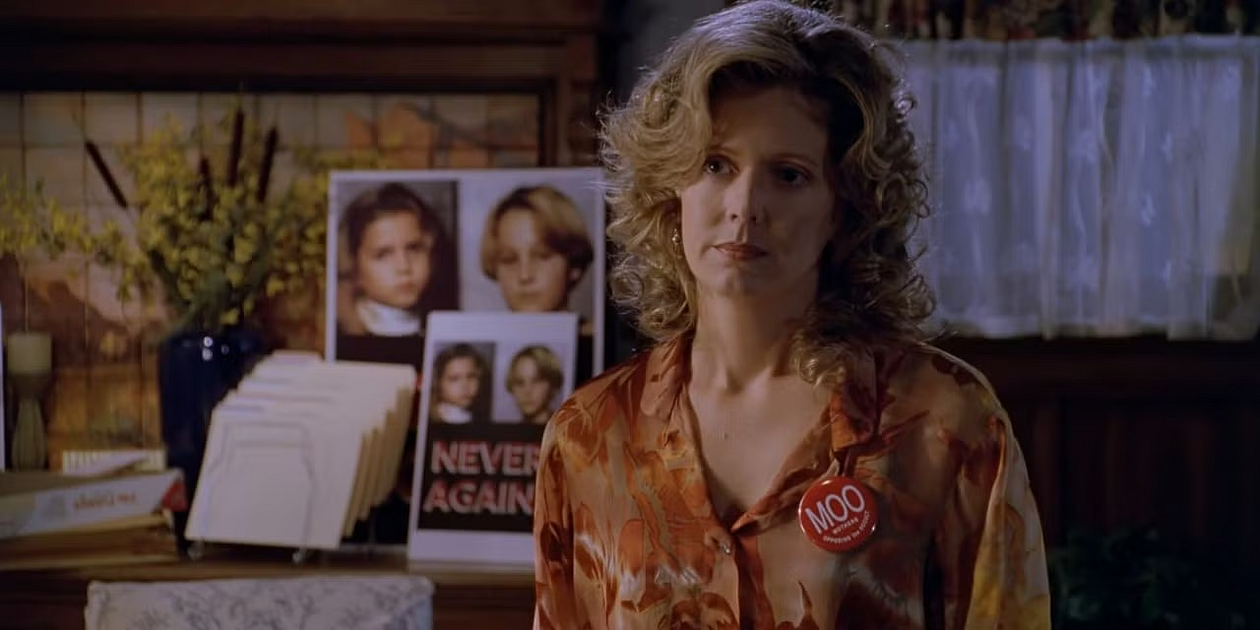

The episode begins when Joyce, accompanying Buffy on one of her patrols (having accepted her daughter’s status as a slayer and harbouring a tentative curiosity to learn more), discovers the bodies of a young boy and girl in a local park. Disturbed, Joyce rallies together Sunnydale’s parents and forms a movement aimed at taking the town back under control from the occult-obsessed youth of Sunnydale High, whom they ultimately consider responsible for the children’s deaths despite any best interests.

When Buffy twigs that little if anything is known about the children, the Scooby gang — Buffy’s in-the-know misfit pals Willow (Alyson Hannigan), Xander (Nicholas Brendon), Oz (Seth Green), former “it-girl” Cordelia (Charisma Carpenter) and librarian Giles (Anthony Head) — suspect dark forces at work. Researching the children, they learn that they’re in actual fact the ghosts of Hansel and Gretel conjured up by demons to sow discord among townspeople once every 50 years. Feeding off the ensuing chaos, the demons thrive “not by destroying men, but by watching men destroy each other,” to quote Giles himself.

Under the children’s sway, and with the help of youth-averse principal Snyder (Armin Shimerman), Joyce has libraries pillaged and witchcraft paraphernalia confiscated by the police, all in the name of purifying the town’s youth and taking back control. Buffy, practicing witch Willow and her wicca friend Amy are then captured in a bonafide witch hunt, tied to stakes buried in mounds of textbooks and — were it not for Giles and Cordelia who intervene and help Buffy break the curse — almost burnt alive.

Despite the episode’s lightly farcical tone, it’s striking how uncannily “Gingerbread” predicts today’s entrenched baby boomer/millennial and gen Z divide and the conspiratorial discourse around “woke” learning material in schools today — itself farcical. Just as feminist, postcolonial and LGBTQ+ education in schools is scapegoated as the source of today’s social ills — supposedly brainwashing “our children” with harmful ideology at the expense of young, innocent lives — so Joyce and her peers view the Scooby gang’s interest in occult and demonic history and witchcraft in Buffy as perverse.

Joyce is of course under the spell of what we would call the humble culture war, a tool used by those in power (in this case Snyder and the authorities) to quash anything that threatens to destabilise conservative establishment ideals. As in the real world, the unstoppable force of societal progression — i.e. Buffy’s fight against the forces of darkness — is rebranded as dangerous “ideology,” perpetuating the divide between marginalised youth and the hegemonic ideals of society’s elders, in the process concealing a version of the world (reality) that parents will out of existence. (In a way, our modern answer to Buffy is perhaps Channel 4’s recent series Generation Z, which sees a small army of Brexit-generation old folks seek out the flesh of the town’s young population).

The episode “Helpless” expands on this divide by honing in on the theme of misogyny. Shifting the needle into much darker territory, it boasts some of Gellar’s finest work on the show as she seamlessly embodies what it is to be alone as a young woman existing in a sadistic and patriarchal system.

Coming immediately after “Gingerbread,” the episode introduces one of Buffy’s most memorable villains — the pill-popping vampire misogynist Kralik (played brilliantly by Jeff Kober), whose mommy issues, perverse humour and love for torture chime with contemporary anxieties surrounding motherhood and reproductive rights in the US today.

The episode follows Buffy when she notices a sudden diminishing of slayer powers. Unbeknownst to her, she is undergoing a rite of passage engineered by the England-based Watchers’ Council, who, lurking in episode’s sidelines, cajole an unwilling Giles — Buffy’s “watcher,” or mentor, and substitute father throughout the show — into hypnotising and injecting her with a power-shredding cocktail of muscle relaxants. According to the Council’s archaic modes, on turning 18 the slayer must be stripped of her powers and in a “time-honoured rite of passage” made to face an especially brutal foe in a specified location — all in the name of testing her innate “self-reliance.” (As per the prophecy, if Buffy were to die, another unsuspecting young “chosen one” would take the reins as the slayer).

But the Council’s plans are turned on their head when Kralik — Buffy’s adversary held at a dilapidated Arms building in preparation for her test — breaks free from his confines and makes the Armoury his very own bloodbath-cum-headquarters.

A charismatic sadist, though free, Kralik carries out his task of facing Buffy. To do so, Kralik playfully draws on the classic fairytale narrative Little Red Riding Hood. The scene is set when, donning the role of Wolf, Kralik finds and taunts a defenceless Buffy/Red Riding Hood (walking home alone from visiting Angel — the absurdity of which Buffy thankfully voices to herself). Giles intervenes and takes Buffy back to the library, not before she loses her bright red coat to Kralik’s grip. Later, hiding on the porch of Buffy’s family home, Kralik uses Buffy’s coat to disguise himself and kidnap Joyce, remixing the identity and gender-play LRRH is known for.

Back at the library, a guilt-ridden Giles confesses to Buffy that she’s the unwitting subject of a time-honoured test and that her opponent, Kralik, is a sociopath renowned for torturing and killing over a dozen women before eventually being committed. Little do they know that as they speak, back at the Armoury, Kralik taunts a bound-and-gagged Joyce. Taking innumerable polaroid snaps of her, he explains with chilling frankness how his penchant for torturing mothers derives from the abuse his own mother inflicted upon him. “I have a problem with mothers, I’m aware of that,” he admits to her wryly, describing how he tortured and killed (or, being a vampire, ate) his own mother as revenge. The grand finale to his twisted fairytale? Killing and turning Buffy only to have her kill Joyce herself, spinning the slayer into his web of brutal matriphagy.

Many interpretations of LRRH consider its story as an analogy for becoming a woman and the state of transition involved in such rites. However, given Whedon’s self-professed fascination with womb envy — the notion that men subconsciously envy a woman’s natural ability to harbour a child and the innate powers of womanhood/maternity it endows her with — it’s possible that the ingestive plot elements of LRRH are used to explore men’s innate misogyny in “Helpless”.

In other words, Kralik’s matricidal blood-drinking mirrors the wolf’s ingestion of Riding Hood, her grandma, and the contents of her basket — a vessel typically positioned in front of her abdomen in illustrations. Together, their consumption of women and their “goods” enact male pregnancies that both deny women of their maternal power they hold, taking it as their own. (Emphasising Kralik’s actual “ingestion” of those he drains, after killing and turning a Council guard, he’s shown noisily sucking the blood from his fingers).

Yet Kralik’s inclusion of Buffy in his matriphagous fantasy, remixing the source material, bears weight on Buffy’s relationship with Joyce. Coming home to find a polaroid of her bound-and-gagged mother on the front door, Buffy is forced to travel to the Armoury and attempt to save the very person who betrayed her — and, if Kralik has his way, kill her as revenge for her abandonment.

Buffy arrives at the Arms building — now a glorified escape room — with nothing but “self-reliance” and her very own basket of goods: an arsenal of weapons. A macabre slasher-style game of hide-and-seek ensues as Buffy searches for Joyce while avoiding being found by Kralik. Notably, the dark, shadowy aesthetic of the Armoury (which has the look of an abandoned home) recalls the dimly-lit showdown of John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween, in which serial killer Michael Myers hunts heroine Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) in an empty suburban house. (It’s perhaps no coincidence that Kralik, like Myers, wears a boilersuit).

Noted for its social commentary on parental absenteeism, Halloween echoes LRRH in its discussion of female adolescence and society’s failure to protect its youth (Red Riding Hood’s own mother is largely absent from the narrative). When, in her search for Joyce, Buffy stumbles across a room plastered wall-to-wall with polaroids of her bound-and-gagged, Kralik forces Buffy to confront her mother’s own absenteeism, exposing their shared helplessness in life; no longer a “guardian” in the strictest sense, Joyce, like Buffy, is her own, fallible person.

Buffy (of course) succeeds at overpowering Kralik, tricking him into drinking holy water to guzzle down his meds with. By doing so, she gives Kralik both what he wants and what will kill him — the contents of her basket and her innate power as a slayer — while cleverly reversing his ingestive obsession onto himself. Watching him burn from the inside, Buffy delivers one of the show’s most iconic lines, denying Kralik her womanhood in the process: “If I was at full slayer power, I’d be punning right about now.”

If only Buffy’s new-found vulnerability as an adult could be shaken off with such cunning. “Helpless” is about Buffy’s entry into an inescapably exploitative adult life. At the episode’s core lies Joyce’s and Giles’ inevitable betrayal as complex adults, often unrecognisable to us on the other side of adolescence. “Who are you?”, a crestfallen Buffy asks Giles when he owns up, a shattering reversal of the question asked of Ken’s slave workers in “Anne.”

Their parental failure opens up the floor to the betrayals young adults face in the wider world and its institutions once thought of as hallowed — chiming with the newly instated US Republican government who, as I write, roll back the once-considered enshrined rights of women, LGBTQ+ people and immigrants. (Since taking power on the 20 January, the Reproductiverights.gov website, a vital resource for pregnant people, has been taken down, whilst Trump is due to revoke federal acknowledgement of transgender identity, declaring in his inaugural speech that “there are only two genders”).

Already Buffy suffers at the decisions of the Watcher’s Council, a male-dominated, antiquated institution reminiscent of the British Conservative party (Whedon spent time growing up in the UK). As if disturbed by the prospect of an autonomous woman surpassing the angelic confines of youth unchallenged, the Council effectively punishes Buffy for reaching adulthood — maintaining the slayer in a cruel, misogynistic sport.

Meanwhile, ever looming in the sidelines of season three is the Trumpian, double-dealing wannabe demon, Mayor Wilkins (played by veteran actor Harry Groener), whose charming wit and seemingly avuncular character make him Buffy’s most popular “Big Bad” amongst fans.

Yet Wilkins’ fascistic distaste for germs and foul language betrays sinister intentions and a virulent distaste of the meddlesome youth. It’s no coincidence that in “Gingerbread” the school’s confiscated books and student possessions are kept at the City Hall, their power a threat to his machinations as Mayor.

His masterplan? Through leveraging Sunnydale’s supernatural forces forging an alliance with the verminous principal Snyder, Wilkins plans on hijacking Buffy’s graduation ceremony as keynote speaker in order to carry out an “Ascension.” That is, during his speech, the Mayor will metamorphose into a giant snake-demon — a demon in its “purest” form untethered by the human body — and feed greedily off the students before him. Despite Buffy’s efforts to stop him, Wilkins succeeds in ascending (complete with some fine ’90s special effects), only to face the Scooby gang and a rallied-up class of ’99 before ultimately being blown to smithereens.

Though he fails, the Mayor’s hijacking of Buffy’s graduation ceremony is a tongue-in-cheek but deeply symbolic (not to mention phallic) display of the predatory neoliberal forces that lay in wait beyond school — a social system that rewards the elite and exploits the vulnerable. (Hence Wilkins’ literal ingestion of students. As if this weren’t enough, in “Band Candy” Wilkins has the town’s adult population cursed in a distraction enabling his team to steal newborns from the hospital and offer them up to a sub-terrestrial sewer demon in return for power).

It’s difficult not to view Wilkins’ rise to power without thinking of Donald Trump’s return to the White House as his very own Ascension proper. While the Mayor’s thirst for unmitigated power and destruction matches that of the sexual predator-cum-leader of the free world, their shared family-man values and chipper personalities both disguise a casually cruel and patriarchal core.

Though less obviously misogynistic than vampire Kralik — or Trump himself — Wilkins is known for his lightly sexualised parental grooming of rogue slayer Faith (Eliza Dushku). Exploiting her vulnerability as a “bad girl” misfit ill-suited for the Scooby gang, Wilkins sharpens Faith into his most powerful weapon in his fight against Buffy: a killer.

And at a closer look, Wilkins shares key characteristics with Kralik. As part of his preparations for the Ascension, the mayor consumes a box of large spider-like creatures that from inside him will cultivate his transformation in time for Graduation Day. Directly recalling the womb envy of Little Red Riding Hood’s ravenous wolf, Wilkins’ consumption closely aligns him with Kralik’s fixation over laying claim to reproductivity, of harnessing the power of motherhood.

Similarly, the Trump administration’s archaic attacks on abortion rights in recent years speak to such paranoia surrounding the ownership of women’s bodies. In 2021, for instance, vice president JD Vance openly characterised the Democrats as “sad,” “childless cat ladies,” invoking the age-old token of woman-as-witch trope. Vance’s words are a telling reversal of Kralik’s hatred of mothers, demonstrating that womb envy stems not only from a woman’s ability to bear children, but fear-inducing power in her decision not to have them in the first place. Indeed, a legacy hallmark of patriarchal ideology is that women must fall into one of two categories: youthful, fertile and willing; or old, sad and bitter.

· · ·

In many ways, Buffy feels written for our times. The monsters you grew up fearing aren’t under your bed. They’re the scheming right-wing politicians that chip away at democracy in order to rise through the ranks and the elusive tech billionaires they’re beholden to, who wield their eye-watering wealth to monopolise the world — to, like Wilkins, ascend.

Writer Jonathan Taplin speaks of the otherworldly pursuits of a small number of male tech billionaires (X and SpaceX owner Elon Musk, investor Peter Thiel and, the latest addition to the dark side, Facebook founder and Meta chief Mark Zuckerberg) that pull the strings of everyday life. Their dystopian endeavours span from outright ruling the world through their digital empires to harnessing immortality, living in outer space to creating a virtual world-cum-crypto-monetised digital hellscape, aka the Metaverse.

No guess as to who gets the magic immortality pill and lives on mars when the world becomes uninhabitable, and who won’t; less investments in the greater good, the intentions of our technogarchic overloads are sheer, untethered abuses of power not unlike the world-ending, trans-dimensional dreams of Buffy’s immortal demons.

Crucially, while Buffy’s social commentary is infinitely vast, it can largely be boiled down to a study of our promethean use of science and technology — often allegorised as dark magic — to rule or transform the world for better or for (much) worse.

Thus, like the Mayor, a great deal of Buffy’s baddies are in fact humans out to exploit Sunnydale’s evil forces for their own gain. Kralik is held as a weapon by the human-led Watcher’s council, remember, while season six’s trio of big baddies — human geeks Warren (Adam Busch), Andrew (Tom Lenk) and Jonathan (Danny Strong) — are precursors to the white American incel (involuntarily celibate) who, fusing their technological knowhow with childish forays in the dark arts, plot to take over the world. (Need I spell out their real-life modern-day counterparts? Ironically, to label vampire Kralik and Mayor Wilkins as equivalents to the nonentities in power today would be an offence to the show’s creators).

And yet the reverse can also be true, with life imitating the horrors presaged in Buffy.

Today’s post-truth political climate, for instance, is in many ways foretold in Buffy’s “ultimate” Big Bad, The First Evil. An incorporeal sum of all evil that predates humans and demons altogether, it takes the form of any dead person or thing but is otherwise a shadowy, spectral entity that haunts Buffy’s seventh and final season — first introduced in season three, however, further cementing the show’s third outing as its most prophetic. In the same way the First predates humans, the spectre of AGI, or artificial general intelligence (AI at its most sophisticated, matching or surpassing human intelligence), in many ways postdates mankind altogether, rendering humans obsolete or even extinct.

The parallels between the two forces are uncanny. The existential dread regarding the spectre of AGI (felt even by its creators) closely mirrors the insurmountable rise of the First early in the season, whose dark connectedness wicca Willow senses in episode one. Just as the First uses its chameleonic powers to deceive or divide its enemies, AI, when not being used to conjure up holograms of the dead, is weaponised to dupe social media users into taking AI-generated, propagandist images as real, genuine information. And quite like artificial neural networks prop up the manosphere by steering harmful and divisive social media content towards users, the First’s physical incarnation and most powerful asset, the femicidal former priest Caleb (Nathan Fillion), is a vicious misogynist who’s collared appearance and intentions of “purifying” women obscure his evil true self.

Because as ever, deception is key. AI is treated by its pluggers like the long-awaited arrival of a revolutionary, quasi-religious force that will save humanity by combating climate change and liberating us from suffering. Though its potential for progress in fields like health and science is undeniable, in reality, the end goal of AI’s unregulated roll-out is to line the pockets of Silicon Valley.

A most sophisticated demon, AI “benevolently” provides its shiny new services for free (getting us all hooked, as was the case with social media), while vampirically draining the work of authors, artists, journalists and researchers with the same level of impunity it pumps out carbon emissions and bleeds reservoirs of the water needed to keep the vast data centres that power it cool. It’s difficult not to demonise such an impending force, one we’d typically associate with a bleak dystopia.

Moreover, through its pillaging of private, copyrighted work, AI threatens to rob us of our human powers of creativity and intellect — the thought of which, as a writer (and human being), leaves me feeling unthinkably helpless, stripped of something I feel integral to my identity and power as a thinking, living individual.

An amalgamation of reckless technological advancement and global warming, AI, in a way, symbolises the greatest betrayal of all the young face today: grafting all your young life to enter an overheating world where the skills you’ve acquired might one day become obsolete, in which you’re outsmarted by a machine. In fact, the eerie acceptance of its “inevitable” existence — as we go about our day-to-day lives mildly accepting the advancement of AI as another one of “those things” — lends itself to the unspoken collective awareness of evil forces in Buffy’s Sunnydale. Could AI be our “Last Evil,” to coin a phrase, signalling the end of the world as we know it?

· · ·

It’s here that I would write about our need to band together in a youth revolt to change the world — how we should cheesily rally together like Sunnydale’s class of ’99 (minus the flamethrowers) and hit the duplicitous undoers of democracy where it hurts. But to write about Buffy’s exploration of real-world political dynamics and not mention its creator Joss Whedon’s behaviour while on set would be remiss.

In 2020, a string of allegations from actors across the “Buffyverse” blew the lid on how Whedon fostered a often brutally toxic work environment. From exploitative 21-hour long shoots, abusive rhetoric levied against the cast and crew and rumours of a vicious fear/revere cult of personality surrounding himself (as well as being a prolific romancer of colleagues and fans, despite being married), Whedon’s on-set world was anything but egalitarian.

So high were the foundations of his genius, however, that Whedon became superhuman. As Buffy writer Rebecca X put it in an interview with Vulture, “I talked about Joss as if he were a human, and people gave me shit for it.” And it’s clear that he revelled in his transcendent role as “creative genius,” regularly mocking scripts passed to him. After reading the suboptimal work of a female writer, he’s alleged to have assembled her and her colleagues for a 90-minute mock lecture in “how not to write a script” — a level of denigration worthy of demon Ken and his army of no ones.

Many of those who bore the brunt of Whedon’s toxicity were the show’s women, with many of Buffy’s female actors coming forward publicly to share their experiences. (That it was an open secret on set that Whedon couldn’t be trusted to be alone in a room with then-teenager Michelle Trachtenberg — who played Dawn in the show, younger sister to Buffy — arguably says enough).

First and chief among those to come forward was Charisma Carpenter (aka the iconic Cordelia in Buffy and its spinoff Angel), who bravely spoke about her experience of Whedon’s “casually cruel” treatment of her on set. According to the actor, pregnant during filming for a later season, Whedon “weaponized her womanhood” by asking outright whether she “was going to keep [the baby],” only to fat-shame further into her pregnancy. Giving birth after that season, Carpenter was “unceremoniously” fired.

(Whedon has denied calling Carpenter fat. However, Sabrina the Teenage Witch creator, Nell Scovell, has stated in her memoir that when she met Whedon in advance of working on Buffy, she was met with the words “Boy, are you fat,” while the above-mentioned Rebecca X also claims to have received the same greeting. Talk about womb envy, which for Whedon seems less a thematic interest than a fetishistic itch played out in the very making of the show).

In fact, given what we now know, Buffy’s long list of troubled male characters doomed to grapple with their innate monstrosity — vampires with souls; conflicted werewolves contending with the beast within them; incel-type high school nerds with a penchant for sex bots and dominating the world — paints a complex picture. It suggests a man perfectly cognisant of his own sexist foibles who capitalised on a generation’s desire to see strong female characters on screen, and carried out perhaps the greatest sleight of hand in TV history: exorcising his demons by writing them into a feminist show as complex male characters and villains, and having a woman kill them by proxy.

For fans, learning of the reality that Buffy came from and just how helpless those involved in its creation must have felt was a great betrayal. That the show was cut from the very social fabric it set out to critique, is a bitter disappointment. But is Buffy a product of one man’s hatred/envy of women? I don’t think so. Lots of extremely talented people worked together to make one of TV’s most trailblazing shows and Whedon alone can’t detract from that.

In “Anne,” when Buffy finds herself face-to-face with Demon-despot Ken in his interdimensional hell-factory, he taunts, “what is hell but the absence of hope?” Regardless of where Buffy’s feminist messaging originates, the show’s recurrent emphasis on reclaiming identity remains more powerful than ever.

In an increasingly unrecognisable world, its tempting feel utterly helpless. Yet Buffy asks us to brazenly be us, to have demands, be heard and fight — even when all hope is lost.

· · ·

This article was first published on Counter Arts on 23 January 2025

Leave a comment