Though far from perfect, Garland’s visceral epic brings the banality of war home to a divided America

It’s a not-too-distant America which, despite being in the throes of a raging civil war, feels somehow recognisable. The Western Forces (WF) of California and Texas are preparing to overthrow a successful but beleaguered authoritarian government led by a third-term president (Nick Offerman, who resembles a Trump-Musk hybrid). On the ground, violence and mayhem sow the streets of the major cities, while gun-toting militia control the spaces in-between — the gas stations, the towns, the disused buildings and the long, largely deserted and perilous roads that join up a broken America.

Against the better judgment of mentor journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), jaded photojournalist Lee (Kirsten Dunst) and Reuters correspondent Joel (Wagner Moura) make the brave decision to traverse such roads and journey from New York to the capital, hoping to interview an allegedly weakened president. That’s not without the addition of a newbie, however. When aspiring young photojournalist, Jessie (Cailee Spaeny) recognises Lee at a suicide bombing in New York, she seizes her opportunity to hitch a ride with her idol and learn the tricks of the trade en route. Despite Lee’s protests regarding her preparedness for the horrors of war, no doubt seeing her younger, more innocent self reflected in Jessie, the more trusting Joel and lovable Sammy succeed at swaying her.

An unlikely family of four thus sets off for Washington, forced, however, to double the length of their journey owing to the precariousness of the landscape. This focused journeying literally removes us from the political, thrusting us instead into the outback of a fractured country. The film’s pace, as we follow them on their 857-mile roundabout journey, is steady and gradual, eschewing (for the most part) the cliches of modern political dramas and dystopian thrillers.

Indeed, the politics of the war — how we got here — aren’t important. Aside from glimpsing the Trumpish president prematurely touting the government’s success at the film’s opening, we need not know anymore. The unthinkable, Garland argues, is already thinkable, mirrored in the brilliant performances of the movie’s seen-it-all media specialists: sarky but determined father-figure Joel; wise and avuncular Sammy, a surrogate grandfather in a world he no longer recognises; and Lee, so fatigued after years documenting war abroad that her response to the arrival of civil war in America is a desultory “here we are.” Context is eerily absent; when Joel asks a sniper the group cross paths with who he’s fighting for, he scoffs, “Someone’s trying to kill us, we’re trying to kill them.”

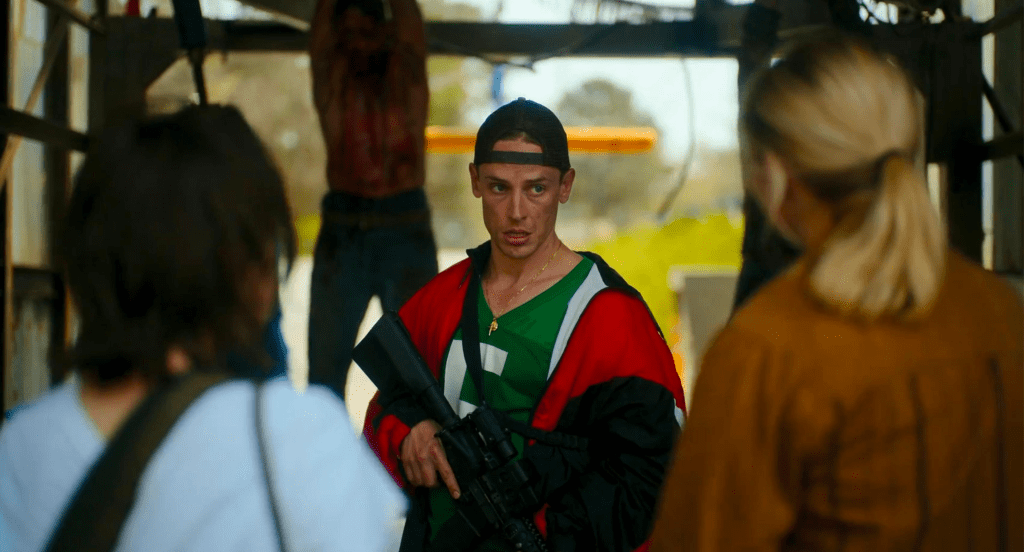

On the surface, Civil War has all the makings of apocalypse horror. Only the “monster” in the scenario isn’t some easily identifiable other (the rabid zombies of 28 Days Later, for instance). More sinister still, they are people — only at their most dangerous: clowns. It’s that familiar-but-unfamiliar uncanniness of the film’s rogue militia members that, like clowns, make them especially formidable, their capacity for dialed-up madness a reflection of that part of the mind within us all we choose to ignore. As Hannah Arendt writes in her seminal Report on the Banality of Evil, observing the trial of German-Austrian nazi official Adolf Eichmann, “Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a ‘monster,’ but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown.”

We glimpsed them ourselves in 2021. They’re the fired-up Trumpists who, spurred on by the free-speech crusaders of X and QAnon, stormed the Capitol in the 6 January Insurrection — face paint, costume and all. Menacing and jocose, they are familiar but not familiar, us but not us. Such is the enemy in Civil War, only now, bolstered by the collapse of democracy, they relish the limelight with as much gusto as the power their rifles and army gear afford them — dangerous dress-up in a real-world, first-person shooter game.

Shunning cliche, Garland paints his civil war as a self-made American phenomenon, punctuating its horror with an acerbic, ironical soundtrack. Scenes of violent unrest, for instance, are juxtaposed with grungy, disaffected electric-rock sounds of Silver Apples. Long vistas of burnt-out or abandoned cars and homes that dot the group’s journey to the capital are backed with the beat-laden churns of the psy-punk band Suicide. Routine executions of prisoners, captured by the WF in a loyalist-held building, are played out to a vivacious De La Soul tune, and as the Americans killed at the hands of Americans are shot, they drop to the ground in slow motion to the up-beat, definitive sound of America; their bodies ripple with an excessive slew of bullets in a cathartic carnival of barbarity not unlike the clownery of the loyalists.

There to capture such barbarity, Jessie takes aim and shoots a weapon of her very own, a camera, Spaeny’s performance expertly treading the line between disturbed and compelled. More than once Garland match-cuts Jessie’s snap-shotting with soldiers’ deployment of firearms, approximating the two instruments. Just as her camera shots will join an already-deluged media landscape, the surplus bullets released from the firearms penetrate the already-dead bodies of loyalist prisoners. What, if anything, can be the function of images and bullets in an eternal circus of violence mediated through images, a buffet of misery at the fingertips of us all? Is our exposure to the destruction of lives and the normalisation of violence it entails to blame perhaps?

Dunst’s superbly monotone performance perfectly embodies this deadening of the image. Speaking with the older/wiser Sammy one night, as bullets light up the sky beyond them, she confesses to thinking that her work covering war overseas “was sending a warning home: ‘Don’t do this’.” Seated on an abandoned sofa, her barely-articulated, exhausted words capture the eventual meaninglessness of her work. Gone are the days of heroic reportage that defined war photographer Lee Miller, whom Jessie figures as her predecessor from another time thanks to their shared name. Miller’s antithesis, her naive pleas fall to dust in the face of the violence before her, perpetrated by people all too accustomed with the sight of suffering.

Civil War might raise interesting questions about the role of photography, but it struggles to bring the complexities of war itself anywhere pertinent. Its underwhelming, conventional third act, pulling the film’s narrative from the periphery to centre on the White House, sacrifices the questioning stance in favour of a more Hollywoodised bang-for-your-buck showdown. Any commentary on the nature of war seems to slip away, swallowed up by gunfire and a rather naive portrayal of photojournalism in action.

Nonetheless, thanks to strong performances and Garland’s pin-drop suspense, Civil War brings to life a world torn not so evenly down the middle to reveal a strangely familiar circus act where meaning is mercurial, facts are irrelevant. Indeed, echoing the shifting static sounds that open the film, the words of Jesse Plemons’ blood-curdlingly sinister performance as a sadistic loyalist summarise the bizarre discombobulation of our times: “What kind of American are you?”.

Time will tell whether or not America will send in the clowns once and for all, regardless of the outcome. But given the volume of buffoonery we’ve witnessed since the film’s release in July (including the former president’s rally-turned-40-minute-dance performance), perhaps it suffices to say that they’ve been with us for some time. Perhaps, to quote Lee herself, “here we are”.

· · ·

This article was first published on the Medium publication Counter Arts on 3 November 2024

Leave a comment