Life choices abound in this poignant transatlantic sequel

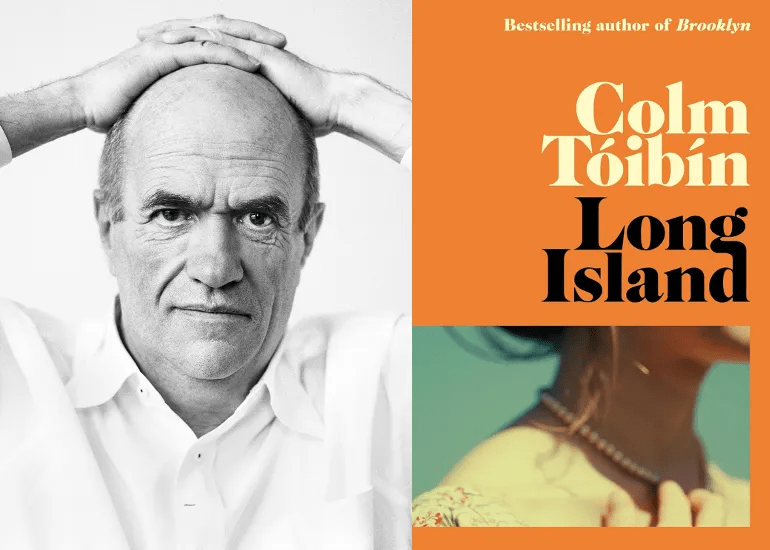

15 years since the publication of Tóibín’s modern classic, Brooklyn, its long-awaited sequel has finally arrived. Appropriately, a similar amount of time has elapsed in the book’s world. Long Island picks up roughly 20 years after determined heroine Eilis was left with no option but to return to her new life in New York when, during a homesick visit home to Ireland following the death of her sister Rose, news of her secret marriage to New Yorker Tony threatened to ruin her impromptu romance with Irishman Jim Farrell — and with it her reputation.

And as ever, reputation is at stake. Once again at the behest of menacing locals, Eilis’ life as a mother of two is upended when, one seemingly average day, an unknown Irishman visits her Long Island home. Revealing that Eilis’ plumber husband Tony has knocked up his wife whilst on the job, the result of which he declares he will simply leave on her doorstep once born, the matter is resolved with under-the-carpet swiftness typical of the community. Now, betrayed, Eilis’ life choices are dramatically thrown into doubt, spurring a return home. Arrangements are quickly made, and Eilis heads back to Enniscorthy where she must reconcile the past — her leaving Jim, settling with Tony and having children — with an unknown future.

If Brooklyn was a landmark immigrant novel, Long Island delves into ‘what could have been’ through Eilis’ odyssey home, a return made all the more layered with the eventual visit from her very much American teenage children, Larry and college-bound Francesca. Yet through the character of best friend and now widow Nancy, Long Island also looks closely at what it is to never move in the first place and attempt to improve one’s lot in an oppressive, dated society. Now secretly courting Jim, the former would-have-been fiance of Eilis, Nancy is near to building a life for herself once again, one complicated, however, by the sudden reappearance of her old friend, whose reassessing of life will rekindle old flames and place Jim at the centre of a high-stakes love triangle.

As with Brooklyn, Long Island is both icily restrained yet deeply perceptive, wielding the plot’s growing dramatic irony with subtlety and grit rarely seen. Tóibín’s blunt prose perfectly evokes the matter-of-fact, steely ways of life native to both Ireland and Italian-immigrant Long Island, homes both to unforgiving and small-town dynamics in which everybody knows everything and everyone. Thus a cool hostility simmers quietly beneath the surface of Eilis’ and Nancy’s lives, a communal sangfroid that, emanating from the page, keeps locals and family members in their places.

In Long Island, for instance, Eilis cannot escape the stifling presence of Tony’s overbearing family (the in-laws live in their same hemmed-in building complex). In the habit of ‘dropping by’ unannounced, they keep the wheels of hushed family and neighbourhood gossip turning. Adding to the invisible current of animosity, moreover, is Eilis’s Irish background, which leads her in-laws to view her as a threat, something to upset the Italian-American harmony. Chip shop owner Nancy, meanwhile, struggles to evade the piercing eyes of Enniscorthy, living out her (perfectly above board) affair with Jim with painstaking care. Ever fearing the town’s panoptic glare and far-reaching gossip, Nancy leads a life removed from the exigent presence of all those around her except Jim.

Our reacquaintance with both Eilis and Nancy, in fact, is symbolically marked by intrusion. “That Irishman has been here again,” notes Eilis’s “insinuating” mother-in-law, referring of course to her husband’s belligerent client. Her words open the book, and represent the essence of Long Island and its predecessor: the uncontrollable, persistent and often life-altering intrusion of others. Later, in her first chapter in the book, back in Enniscorthy Nancy routinely ignores the menacing stares and comments of the town bank manager and his wife who condemn her for the sounds, sights and smells that spill out from her chip shop. Eventually shooing them off, not without the threat of their possible return for more, she must then deal with the local drunks who later demand she reopen after closing, even “banging forcefully on the glass” and refusing to leave unless supplied with chips. Open or closed, Nancy cannot win, a marker of her life as a working woman in ’70s Ireland.

It’s no coincidence, then, that both women yearn for and relish seclusion in their respective lives, away from the interminable judging of the tradition-bound cultures of Ireland and Italian America in which conformity rules. Where Brooklyn was a metonym for escape, an end goal envisaged by Eilis and female immigrants like her in search of an independent life, Ireland here becomes yet another opportunity to escape, as hinted at through the wordplay with Long Ire/Island. Even then, once back in the strict confines of Enniscorthy, Eilis nonetheless delights in staying at her brother’s remote coastal home, removed from her mother’s home and her somewhat begrudging welcome back (a reception mirrored in her distaste for the white goods Eilis insists on buying her mother on returning home, tokens of the flashy life she left for in the first place). The slice of life Nancy craves, on the other hand, takes the form of an imaginary bungalow far flung from Enniscorthy along the River Slaney. Nancy plots — literally — for life free from the “enclosed, watched-over places” of Enniscorthy.

It’s tempting at times to view Eilis and Nancy as being somewhat hollowed out, or passive, not wholly present or distinguishable on the page. Yet being so pushed and pulled by the forces of those around them, so oppressed in their own ways, this is exactly the point. As the pair vie for freedom, Eilis and Nancy are nullified, emptied out by the judgements and demands of others. Desperate for self-realisation, for lives of their own, they must both make tough decisions whilst balancing the fragile needs of children, friends, family — and one another. Master of the fork in the road, Tóibín succeeds beautifully at weaving a complex and historical narrative onto the page with insight and delicacy, teasingly, however, refusing to reveal all of his cards.

⋅ ⋅ ⋅

This article was first published in Counter Arts on 2 September 2024.

Leave a comment