History and life are two sides of the same coin in this fragmented and far-reaching coming-of-age epic

“An entire political system could opt for self-imposed distress — he had once spent some time in East Berlin. Marriage, a machine for two, presented king-sized possibilities, all variants of the folie à deux.”

— Ian McEwan, ‘Lessons’

Writing in May, historian and critic Timothy Garton Ash opined that “in history, as in romance, beginnings matter – so what we do now will be crucial in shaping the future.” Investigating the recent trend of attempting to cram our globalised, endangered and increasingly complex, war-torn times under one cohesive “age” (e.g. “The Age of Revolutions”, “The Age of the Strongman” “The Age of AI,” of… “amorality, energy insecurity, impunity, America first, great-power distraction and climate disaster”), he’s perhaps correct in baptising our modern age simply as “the age of confusion”.

Ash’s words make for an unusual subtitle for an article unpicking these uncertain times we live in, but less so when we consider his role in editing Ian McEwan’s latest work of fiction, Lessons (2022). Following the somewhat stymied life of a man juggling his wife’s recent disappearance whilst struggling with life-long memories of an abusive piano teacher, McEwan ambitiously equates a broken but privileged life with our troubled, amnesiac world — both of which are united by a lingering identity crisis. Like life, McEwan asserts, history is messy and volatile, a fraught game of hopes and determination, happenstance and misfortune.

Ever at the mercy of the parents, teachers, lovers, friends and partners around him, the rather passive Roland moves through life as though pulled along on a conveyor belt, lacking clear demarcations or any sense of trajectory. And so when, in 1986, Roland’s wife Alissa abandons her family and relocates to her native Germany to pursue dreams of becoming a serious author, the mood is oddly anticlimactic, non-seismic (her letter as consequential as a perfunctory “gone to get milk” note). Likewise, only five years later, subconsciously searching for his missing wife in Berlin he is witness to the fall of the Berlin wall (something of a metaphor for marriage throughout the book). At first perceiving the sense of political liberation in the faces of the excited, newly unified Germans, he’s soon struck by a sense of mutual boredom, any sense of a new dawn quickly draining away.

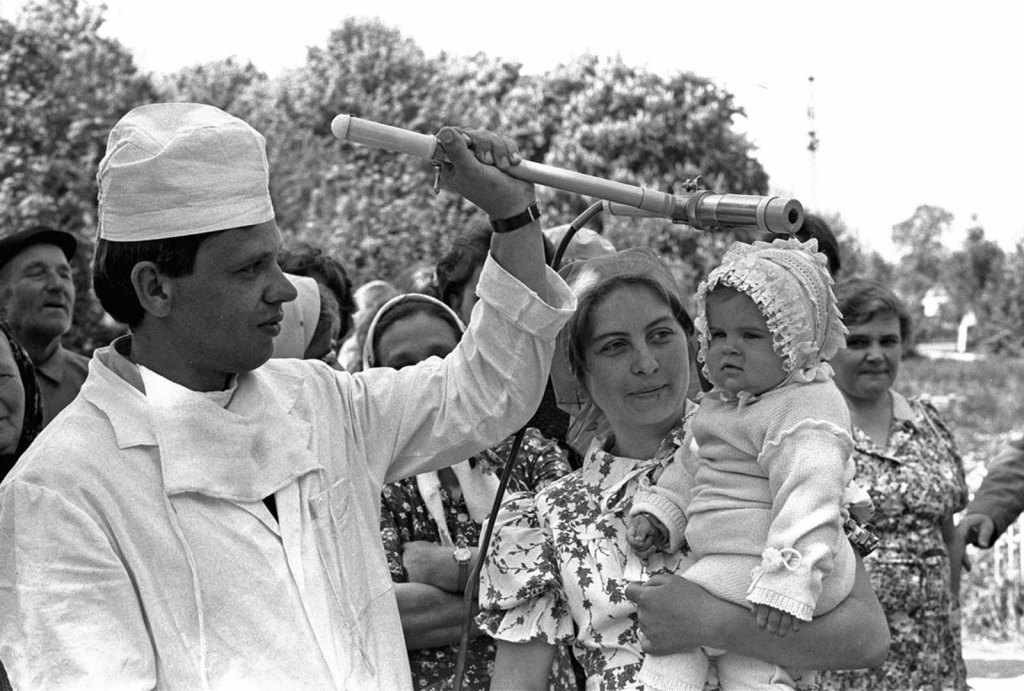

Life goes on, the conveyor belt churns forward, and Roland and baby Lawrence, following Alissa’s departure, adapt to a new life. They do so just as they adapt to the encroaching toxic smog, rumoured, rather sensationally, to be reaching the UK — ripples from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster 1,300 miles away — by boarding up the windows and avoiding tap water. (Such preparations would prove futile, the clouds being a threat only to western extremities of the UK).

Life, like history, is defined by such ripples. McEwen poetically mirrors the far reaching effects of such geo-politics — Chernobyl here heralding the Cold War which will function centrally to the novel much later — with the echoes of Roland’s traumatic past: namely, the ever-present memories of the sexually abusive piano teacher, Miss Conell, during his time at boarding school. Preying on young Roland’s vulnerability as an army child far-removed from his parents (stationed in Libya some 2,400 miles away), she will groom and manipulate him into submission — even going as far as to erotically imprison him in her home one summer break, depriving him of all possessions save for his pyjamas.

But it’s one particular “insomniac memory” of Miss Conell which opens the book itself and which haunts him every day. Laid with his napping son in the present, he recollects, or rather, is breached once again with the distinct memory of her attempts at ingraining in the 11-year-old “an easy rippling sound” on the piano during an early first lesson. Memory and time are porous as past events flow freely, pushing to the surface and refusing to die even if they lack the detail they once had.

Accordingly, Lessons rejects any linearity in narrative, time being neither here nor there. We shift back and forth between two temporalities, each beginning with the respective traumas of Miss Conell and gone-girl wife Alissa (whose disappearance we know little about but which remains underwhelmingly non-suspicious). Thus “Miss Cornell, the piano teacher who meddled in his affairs by novel means over distances of time and place; Alissa Baines, née Eberhardt, beloved wife, who held him in a headlock from wherever she was,” the narrator muses in free indirect speech reminiscent of the classic roman d’apprentissage.

It’s no coincidence that Roland identifies with the fanciful young Frédéric Moreau of Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale, the seminal oeuvre of the coming-of-age canon which he reads as an adult seeking to claw back his studies. Seeing himself reflected in Moreau’s love affair with an older woman at the age of 14, Roland’s story certainly echoes the plight of Flaubert’s Bovarian protagonist (who too sees himself reflected in the characters of 18th- and 19th- Romantic literature). Yet challenging the formula of the classic coming-of-age, McEwan’s division of temporalities — Roland’s younger and adult self — thwarts or perhaps modernises its structure. Through the narrative’s complexity, McEwan exposes a certain placelessness to time and memory as we experience it; life’s lessons resist our attempts at blindly tying loose ends together into a picturesque bow typical of the coming-of-age.

On the one hand, if we can divide the book in two, we progress from Roland’s traumatic time at boarding school to his years as a bright but unqualified, rootless young man based in London. It’s here that he embarks on various careers, plays the field and eventually meets German course teacher Alissa — with whom he travels to Germany with hopes of learning more about her mother’s time with the anti-nazi cladestine group, the White Rose. Like the novel’s delving into the past lives of Roland’s own parents, the biography of Alissa’s mother is one of several lengthy tangents into the past which further destabilise the narrative.

On the other hand, years later, we follow Roland’s adult journey raising young Lawrence alone, surrounded by the like-minded London politicos (teachers, doctors, creatives) that form his circle of friends and who support him following Alissa’s disappearance. Donning the role of copywriter, tennis coach, hotel pianist, published poet, father and eternal student, he continues, in a way, to inhabit the role of the pyjama-wearing youth Miss Conell so ardently desired him to be. Ever searching for answers (and a fixed, unified identity), Roland oscillates between compassion and rage, stability and rootlessness.

Despite its dispersed layering, taking us across time periods, histories, languages and continents, the book nonetheless progresses towards a vague finish line, culminating in the post-pandemic world facing an uncertain future we live in today. Moreover, McEwan anchors us with the inclusion of historical events, charting (with a historical realism which borders on straight-up autobiography) national fears of the atomic bomb during Roland’s youth through to contemporary issues like Brexit, the pandemic and the unravelling climate crisis. Though McEwan’s political view seeps through every page, the book nonetheless remains refreshingly objective — the inaction and injustice which taint modern life speaking for itself matter-of-factly.

First published in 2022 in the wake of Putin’s reignited military campaign against Ukraine (and by extension, the West), Lessons emerged at a time of resurgence of Soviet interest, one that only continues to grow today. The global identity crisis Garton Ash speaks of, of course, mirrors Roland’s own — not to mention his inability to, or fear of, confronting the past. What have we learnt, from an illustrative “long” 20th century? When the newly-convicted Trump may still rerun for president; when Russia sets its eyes westward once again, prompting fears of a second Iron Curtain; when a populist wave settles over Europe like a toxic cloud once again; and when war continues to blight Gaza, all to the backdrop of a melting, pandemic-teetering world, it’s easy to surmise, not very much at all.

Perhaps the answer to who we really are — as an individual or collective — lies in facing up to the past in lieu of hurtling towards vague promises of success. Roland, in his search for an identity, follows an “obscure trail of an exquisite idea that could lead to a lucky narrowing, to a fiery point, a sudden focus of pure light to illuminate a first line.” It’s this obsession with finding a fiery point, with achieving the sublime, which blinds Roland and his literary counterpart Frédéric Moreau. Meanwhile, the naive and simplistic quest for glory plagues modern powers today, apparent in our disdain for the ordinary, “the commonplace” issues which affect us every day, in favour of the relentless pursuit of the good old days (all, ironically, while ignoring the lessons of the past made plain in the textbooks). We don’t make history; we are history, and history is us.

It’s in this eternal distraction that our lot as pyjama-wearing, naive creatures incapable of both moving forward and looking to the past, is revealed. There lies our inability to look confidently at the past and learn, to dismiss the ripples of the past which haunt us everyday but which we ignore: home truths, lessons never truly learnt but which Roland Baines must face if he’s to progress in this rewarding, complex story. On the 80th anniversary of the Normandy landings, when history looms large but painfully lost, the truth yearns to be heard once again. ∎

Leave a comment