An intimate portrayal of conflict, shame and gay love during World War I.

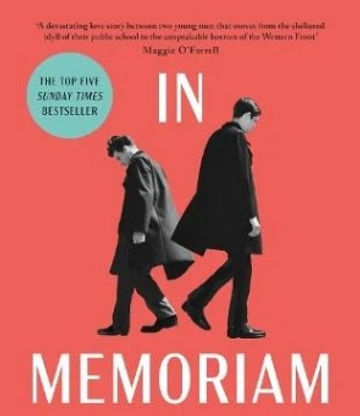

In Alice Winn’s dazzling debut, In Memoriam, we follow the closeted, fraught relationship of Ellwood and Gaunt, one a beautiful but naive Tennyson-reciting patriot, and the other, an austere, German-descending war-skeptic. Torn from the safe confines of their Wiltshire public school, Preshute, they face the ultimate coming of age: Fighting for their country. When Gaunt enlists, spurred on by an unbending, somewhat masochistic sense of duty, he is later followed by Ellwood, who voluntarily enlists early armed with chivalrous notions of fighting the enemy. Yet removed from the Eton-esque confines of Preshute and thrusted into what would be a devastatingly brutal war, separately they must navigate the trenches and the battlefield as closeted gay men. A story of repressed yearning, simmering conflict and the perils of glorification, In Memoriam offers a layered exploration into gay male intimacy and a harrowing glimpse into life on the front.

The book’s title borrows from Tennyson’s “In Memoriam A.H.H.,” an elegy to the premature death of his close friend and potential, if at least symbolical, lover, fellow poet and Cambridge alumnus, Arthur Henry Hallam. (Hallam was even alleged to have professed a love for Tennyson’s sister, a triangling mirrored in the book as Ellwood professes his intentions to marry Gaunt’s sister, Maud). More than this, In Memoriam A. H. H. was written as a lamentation of the changing Victorian world Tennyson faced, one in which advances in natural history coincided with a dwindling of Christian faith. This spurred a growing awareness of a lack of “divine direction” in the world, a collapse of faith echoed in the crisis of faith brought on by the horrors of modern warfare — a brutality to challenge the chivalrous perceptions of war which preceded it.

It’s with much dramatic irony, then, that we witness the naively patriotic tangents of Ellwood, whose glorified perceptions of war we’re made aware of from the get-go. In the book’s opening lines, we meet Ellwood as he pretends to gallantly shoot at the lives of his schoolmates — who he imagines as Germans — from the balcony of his Preshute bedroom. Placing violence firmly as one of In Memoriam’s dominant themes, Winn tightly weaves a sense of aggression into its pages, a certain rage imbued with every sentence:

“It had been years since Ellwood bullied anyone, but gaunt knew he was still ashamed of the vein of ungovernable violence that burnt through him. Just last term, Gaunt had seen him cry tears of rage when he lost a cricket match. Gaunt hadn’t cried since he was nine.”

Male relations, whether in the form of public school frenemies or out on the battlefield, are fraught with a repressed tension. Even before the boys enlist, conflict is played out in the form of schoolyard spats, brotherly roughhousing, and the bullish, late-night hazing of juniors; aggression is the common language spoken by the boys of Preschute, a demonstration of assumed hierarchical superiority and assurance against, or substitute for, any undue intimacy.

For Ellwood and Gaunt, their pugnaciousness likewise negates instances of queer sexual attraction or intimacy between the pair. Ensconced within close confines of public school, they seem to flit uncontrollably between aggression and intimacy, to the point where the two become blurred, if not merged. Thus when Gaunt lashes out at Ellwood and breaks his nose, “his heart soars” — an attack he later looks back at somewhat fondly in a letter to Gaunt. Moreover, covert acts of gay sex at Preschute are disguised by signs of physical acts of violence, the black eyes he asks to receive from partners denoting run-of-the-mill, laddish play-fighting — nothing to see here. Here, Winn deftly hightlights the queer shame which any closeted gay or bisexual man would have felt in early 20th-century England (let alone at the front, where it’s estimated that at least 230 male soldiers were court-martialled and sent to prison for homosexuel acts).

By the time both have enlisted, the politics of Ellwood and Gaunt’s volatile relationship is mirrored in the geopolitics of the ensuing war between England (the Allies) and Germany. War is perhaps the ultimate substitute for diplomacy, rationalised conversation — a form of communication altogether to feminine, intimate, perhaps, and which the boys of Preschute are taught to negate. But inevitably, when confronted with the unprecedented onslaught of the battlefield, the apparent heroism found in the boys’ adolescent belligerence is quickly shattered and violence is shown to be what it really is: The perpetual, senseless killing of men. Winn eloquently charts the grinding down of such idealised chivalry faced with the banal horrors of war, subverting the romanticised views embodied in Ellwood — who himself ironically reveals as much in a letter to Gaunt. Quoting Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade”, he end his correspondence thus:

“‘When can their glory fade,

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade

Noble six hundred!’

Did you hear that Rupert Brooke died? Infected mosquito bite on his way to Gallipoli.

Ellwood.”

Naturally, where Ellwood was once able to reel off quotes from the likes of Keats, Shakespeare and Tennyson, Romantic symbols of a mystically divine Britain, he is scarcely able to recite a single line from his arsenal of literary heroes once acquainted with the War. That Winn subverts notions of patriotic chivalry in the process makes In Memoriam a topical read, the very longing for an imperial, national identity envisaged by Ellwood exists today. Brexit is a testament to this — proof of a collective, nostalgic yearning for a time when Britain dominated the world, Britain as myth. (Moreover, the parallels In Memoriam strikes with Russia’s war in Ukraine — Putin’s yearning to be the great Russian empire it once was — speak for themselves).

Winn succeeds at painting a bleak picture of the War which, despite its countless retellings, never fails to incite horror. Whether describing the colour and consistency of a soldier’s brains, pasted over the face of another, or the smell of rotting corpses whose bones will later jut out from the bloodied earth, Winn writes with a vivid, disturbing realism. And she writes with historical rigour, too. The sandbags used as defence against artillery rot, much to the confusion of Ellwood; this is because, after so much killing, the sand becomes a sickly emulsion of human remains and debris.

As the book progresses, the war intensifies and Ellwood and Gaunt become seasoned officers. Tensions are ramped up as the stakes are raised, seeing the pair weather high-octane battles, nail-biting periods of separation and fraught attempts at fleeing prisons of war. Yet, demonstrating her versatility, Winn just as skilfully succeeds at conveying the bleak, booze-riddled boredom the soldiers must endure between battles, offering insights into the war perhaps not seen since R. C. Sheriff’s landmark play, Journey’s End. Through it all, the momentum is largely sustained, and from chapter to chapter we’re left on the edge of our seat.

It has to be said that In Memoriam would perhaps have felt a degree more nuanced had it centred, at least in part, on the lives of working-class soldiers, as opposed to focusing wholly on the upper-class echelons of Britain’s elite. This would indeed have added a refreshing dimension to the at times toffish dialogue and the plummy characterisations of Ellwood, Gaunt and their school/war peers, and by not doing so, the book unintentionally possesses something of an Etonian quality. Nonetheless, In Memorian is a powerful, epic exploration of opposing forces — beauty and ugliness; glory and shame; love and hate; freedom and confinement — which truly captivates. It is a painful lesson in how our inability to communicate plagues us. Be it our reliance upon nationalistic ideals — ever present today — or our inability to profess our love, we clip our wings in never speaking the truth, or indeed, never speaking at all. ∎

Leave a comment