Apple TV’s pioneering series Severance offers a dystopian foray into corporate hell and the gaslighting forces at work behind it

“Who are you…?

Who are you…?

Who are you…?”

Such are the words that open Apple TV’s masterful series, Severance. Bleated tinnily over a 70’s-style intercom, they’re uttered by protagonist Mark (Adam Scott), the newly promoted Senior Macrodata Refiner at Lumon Industries. As Mark’s voice rings out, we see the unconscious body of a woman, lying face-down on a lacquered, oblong conference table, donning her finest work attire. Regaining consciousness to discover that she has no clue who or where she is, Helly R. (Britt Lower) is about to learn that she has been “severed”—and not in the traditional sense of the term. Thanks to biotech giant Lumon Industries and its pioneering technology, a chip has been implanted into her brain, dividing her work-self and personal life. In other words, Helly now has two selves, neither of which know the other: her so-called “innie,” the memory-wiped, clean-slate version of herself who must now work down in the depths of Lumon’s mysterious Macrodata Refining department, and her “outie,” Helly R.’s true self outside of work, the one who knowingly chose to undergo “severance” in the name of improved work-life balance — or so she’s told. As such, every morning, on descending the lift down to Lumon’s subterranean network of offices, Helly R. and her colleagues have all knowledge of their outside, real self wiped, and resume their work life as their severed innie.

But the stubborn, disbelieving new starter, confronted with the drudgery of data refinery and ever-suspecting Lumon’s true intentions, is quick to want out. Desperately transporting messages to the outside world and even putting her life in danger in the process (no written communication of any kind can pass by the lift’s rigorous code-sensors), Helly stops at nothing to convince her outie, the only person who can grant her permission to leave, of the misery she undergoes at Lumon. Her remonstrance soon spreads among her obliging peers, gradually reaching the work-happy Mark S., severed in an attempt to provide respite from the pain of losing his wife; the cocky, perk-loving, and target-obsessed Dylan G.; and the rule-abiding Irving, whose sickly obsequiousness and devotion to workplace policy and rules make him the office square.

Tasked with assorting an Excel-style sheet of infinite wiggling numbers on an enjoyably retrograde computer, the refiners must graze the figures until they come across a particular group which, eliciting an unusual, enticing sense of fear, they must sort into various bins at the bottom of their screen. They are, quite literally, number crunchers and are rewarded for the higher volume of numbers they assort, winning pitiful little prizes as they do so. What data the team “refines” on their bulky desktops is never elucidated, and any attempt to pinpoint this leads nowhere. The sacrificing of goats? Hits on high-profile figures?

As we quickly learn, this doesn’t matter. All that does is that the emotions and sensations of work are simulated — namely, the “thrill” of a deal or meeting to-the-wire deadlines, feelings mimicked in the refiners’ fear-inducing number crunching. Monitored closely by Lumon’s seniors, most notably by Mark’s boss, the tightly-wound Harmony Cobel (Patricia Arquette), we quickly sense that the severed workers of Lumon, void of an actual purpose, are part of something far more insidious (Guinea pigs, perhaps, for the severance chip). But through its bizarre mimicry of the workplace, Severance delves deep beyond the surface of work to highlight the seemingly blind devotion to work we exhibit in today’s hyper-capitalist society. In doing so, it reveals corporate work as the meaningless, alienating thing it has come to be: A hollow, endless process of shifting numbers it very often is, or which it at least resembles for anyone sitting in front of a computer for eight hours or more a day. As Helly asks herself during her induction, with no small amount of sarcasm, “My job is to scroll through this spreadsheet and look for numbers that are scary?”. Failing to produce anything tangible or worthwhile, work for the Macrodata Refiners is as vacuous as the interminable, labyrinthine corridors they must traverse between shifts, sterile paths leading nowhere.

As well as mimicking workplace thrill-factor, Lumin stages typical workplace rituals we’re all familiar with, only in a bizarre, somewhat surreal fashion. Office parties, for instance, take the form of waffle bonanzas and celebratory egg-themed parties (pulsing disco lights and all). Workplace camaraderie, meanwhile, takes the form of awkward team photos, outlandish, target-hitting gifts (think coffee cosies, finger socks and laser-etched crystals). Office frivolity has never looked so strange, yet such awkward, Americanised workplace traditions, removed from the real workplace, remind us of their pitiful, contrived nature — so much so that we’re moved to reconsider the bizarre workplace rituals we partaken in ourselves.

Moreover, Lumon’s recourse to employee wellness, reward and punishment, arguably the three central pillars of modern work, represents something equally recognisable — and altogether darker. Take Mark’s routine trips to the wellness room, where he’s sent when his performance is deemed on the wane. Led by the eccentric Ms. Casey (Dichen Lachman), the sessions consist of a seemingly endless stream of observations vis-à-vis Mark’s outie — his true self. “Your outie is kind… Your outie appreciates nature… Your outie likes cake,” she reassures him, reading ASMR-like from a list of oddly specific attributes, all to a soothing soundtrack and in the shadow of a large indoor plant. As before, the customary workplace ingredients are here, only this time in the context of workplace wellbeing: The conviction that we are “somebody” outside of work or that we have at least a fulfilling life beyond it. The obligatory presence of the office plant, that trusty metonym for the natural word reminding workers of a greener, more serene life we can look forward to at the weekend (and which employees can catch a glimpse of thanks to the digital window above them). The pseudo-psychological inclusion of ethereal music which intends to ground its listener in the present moment, a sense of presence any modern worker today would be hard-pressed to identify with, not least from the office building.

As the show develops and we’re immersed further into the shadowy world of Lumon, life there gradually begins to feel like less of a workplace than a dangerous cult. This thing we call “work” has become the dominant religion in Western culture. Take the workers’ blind adulation of great figures, most notably the deceased founding father of Lumon Industries, Kier Eagan, whose omnipresence at Lumon mirrors that of Jesus. The previous CEOs of Lumon are likewise revered, with their giant statues standing tall in “The Perpetuity Room” (where staff are brought for hitting targets or much-needed boosts in team morale). Imbued with a religious quality, the statues cement the CEOs as saints to be worshiped eternally, the pre-recorded quotes they’re alleged to have come out with, played automatically as employees approach them, resembling inspirational quotes from the Bible.

Likewise, when Helly R. is sent to the so-called “Break Room” for bad behaviour, workplace disobedience becomes a substitute for everyday sin. Forced to repeat a profoundly self-denigrating paragraph over a thousand times until she is deemed to be genuinely repentant enough, she is “broken” into submission. “Forgive me for the harm I have caused this world. None may atone for my actions but me and only in me shall their stain live on. I am thankful to have been caught, my fall cut short by those with wizened hands. All I can be is sorry, and that is all I am,” she is made to repeat, her lines chiming with the subservient nature of a confessional. That she reads from a giant screen erected before her, dividing herself and the authoritarian, un-severed supervisor Milchick (Tramell Tillman) and thus mimicking the structure of a confession booth, only confirms this.

Severance thus poses bold questions regarding work and how we unquestioningly sign away our lives to employers. Indeed, the self-obliterating language Helly is made to recite quite eerily echoes the compliant nature of any given employment contract. (You might say that work-related policy and law are the modern-day substitutes for the 10 commandments; read your job contract up close, and you are hit with the sheer obliteration of autonomy and will). After all, doesn’t the person we’re expected to be in the workplace – an obedient, flexible, hardworking person ready to muck in and be part of the fold – closely resemble the devout Christian?

Perhaps it’s a very Catholic brand of guilt, then, that haunts the rule-abiding, Eagan-worshipping Irving. Having taken to drifting off on the job, Irving begins to experience horrific nightmares in which a thick black oil oozes down from the office ceiling to engulf his work cubicle and him with it — not before seeping out from the eyes of his concerned colleagues. It’s later revealed that Irving’s outie spends the bulk of his spare time obsessively painting and re-painting nightmarish illustrations of the hallowed, rarely discussed Testing Room entrance (a long, dark corridor with a hellish red light at its end) – painted in an oozing, oily black acrylic, the same sickly, far-reaching goo which threatens to swallow him whole in the office. And it’s no accident that the substance which threatens to consume Irving is oil-like in consistency and colour, given oil’s near-religious status as a symbol of modern rampant capitalism, a measure by which much of the market exists. After all, Lumon’s logo is stylised to contain a large, thick droplet in its design. Guilt (or the mere anticipation of guilt) and adulation of the great souls who came before us are the two quasi-religious forces that coax Lumon’s severed workforce, between which poor Irving is miserably entrenched.

The gaslighting forces wielded by Lumon, veiled in the workplace trappings of wellness, seemingly rewarding work, and a wholesome “work family,” speaks to the tyrannical power wielded by the tech leaders of today — and our powerlessness faced with it. With the latest developments in artificial intelligence placing the fate of millions of workers on the line, Severance comes at a time of huge industrial change. Just as Silicon Valley tout the life-saving, world-improving virtues of ChatGPT and Dall-e 2 while profiteering from our personal data and work and risking the mass redundancy of innumerable people, Lumon Industries prepares to advertise to the world the benefits of undergoing severance while quietly coaxing its participants (and future participants, perhaps willingly or not) into blind submission.

Discussing the threats posed by AI today, Andrew Keen quotes 20th-century Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein when he says, “Philosophical problems arise when language goes on holiday.” It’s telling that, chez Lumon, forms of written communication, or, more broadly, creativity, are repressed or altogether censored. Take for example the seemingly revolutionary self-help book, The You You Are, written by Mark’s anti-severance outie-life brother-in-law. Touting the virtues of life beyond all-consuming work with sensational teachings on the independence of the self, the book is read surreptitiously by Mark as he begins to doubt his life as a confined, severed refiner. Or take the forbidden act of communicating with the outside world the severed Lumon employees must endure, and the identity-less employee ID cards their innies must don, blank but for the Lumon logo in another demonstration of the refiners total obliteration of the self. Lastly, consider Petey’s map which attempts to determine the layout of Lumon’s subterranean network of offices. Hand-drawn by his formerly severed work friend and Lumon skeptic, Petey, it is discovered by Mark who finds it stowed away in the reverse of a team photo. Mark subsequently holds onto the contraband map and uses it as he quietly attempts to make sense of Lumon’s true agenda.

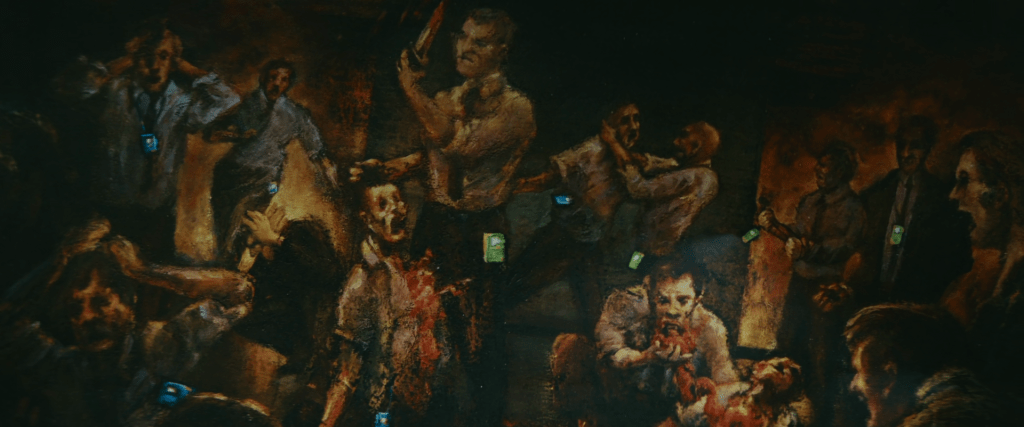

The threats to language posed by AI resonate with this censorship. The company’s efforts to cancel the identity of its staff, moreover, are mirrored in the sense of creative redundancy humanity faces today. There’s an alarming sense of redundancy at play here in both the dystopian world of Severance and the real world we inhabit today: A redundancy of the self and our creative faculties—that which makes us so human, but which makes the tech (world) leaders of today grimace. Creativity, logic and reason, after all, are the critical tools we must hold dear but which Silicon Valley will stop at nothing to cancel out. Moreover, the artwork featured in Severance—pieces selected and assembled by the O&D Department and hung throughout the offices—are mere rehashings of classical works of art, or at least of the style in which they were created.

Interestingly, artwork produced by artificial intelligence functions very much in the same way, riffing off of existing artwork and style. The painting Kier Invites You to Drink of His Water, for instance, depicting a lone Romantic figure looking out over a vast pastoral scene, is an obvious reiteration of Friedrich’s 1818 Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, while the infamously Goyesque painting The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design is an assumed retelling of Greco’s 1658 Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple. It’s the latter which is truly evocative of AI-produced artwork. The painting illustrates the severed workers in a violent, harrowing brawl, yet the way in which the Lumon ID badges are depicted so blatantly is highly evocative of an AI-generated image with the prompt: “Create me a painting in the style of Goya which depicts Lumon workers in the midst of a violent biblical scene”. The presence of such artworks speak to and only confirm the way in which Lumon, and by extension corporate power, can —or will soon be able to— recreate, post-edit and monopolise the works of others and claim them as their own.

Human logic — our workings out — is made potentially obsolete. Much in the same way the genuine identities of the severed colleagues of Lumon are perceived as a threat (Milchick and Cobel go to extraordinary lengths to ensure both are distinct), human reasoning, and the ability to deduce for oneself with language, perhaps, is today being severed from us. What better way of preventing current and future generations from reading, critiquing, deducing, and revolting than to roll out an unregulated app, free and accessible to most of the Western, which supposedly “does all the work for you” in circumnavigating human reason?

Just as Severance hints that Lumon Industry’s infamous chips may be used for much darker purposes (we’re holding out for more of this in the much anticipated but troubled season two), AI programmes like ChatGPT and Dall-e 2 will inevitably be used for ominous ends, as they indeed already are. Either way, Severance aptly taps into how technology, in the hands of the powerful, might attempt to reduce us to nothing. To answer Mark’s all-important question to the unconscious Helly at the start of the show, “Who are you?”, the answer simply is no one. Emptied of her true self, Helly is reduced to a mere receptacle — a blank canvas upon which the invisible tech giants above her might brandish with their propaganda, just as the repentant words she is made to recite in the Break Room anoint her as the sinner she is perceived to be. ∎

Leave a comment