It’s style over substance in this woefully unoriginal psycho-thriller even a top-rate cast can’t save

*Contains spoilers*

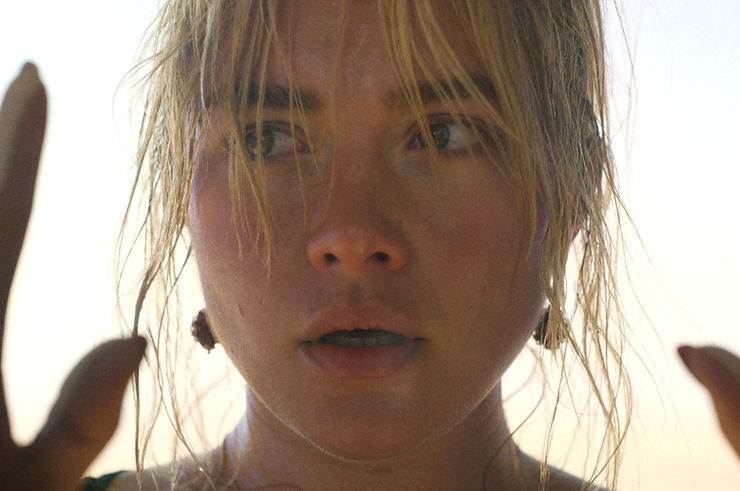

Olivia Wilde’s much anticipated and fussed-over second turn at directing has the suburban walls closing in on its suspecting heroine, Alice (Florence Pugh), caught in the mid-century Stepford Wives’ nightmare that is ‘the Victory Project’. We follow Pugh, who after witnessing the erratic and alarming behaviour of her friend and fellow wife, embarks on a dangerous journey to understand what, exactly, Victory is and her role within it as the doting housewife. Thrust into a familiar who-can-she-trust plot, Alice must fight against the seemingly better judgement of her unsuspecting girlfriends, her charming 9-5 husband, Jack (played by an incongruous Harry Styles), and the mysterious, handsome founder of Victory, Frank (Chris Pine). Yet burdened with a reliance on other key works of its genre and a half-baked, drawn-out plotline, Don’t Worry Darling fails to live up to its hype.

Hitting viewers first off is the film’s glamourously stylised costume and set design, an unequivocal homage to 50s aesthetic which succeeds at drawing you in. Yet as Alice begins to sense cracks in her seemingly idyllic life and we are plunged into predictably claustrophobic psychological-thriller territory (think hallucinations, nightmares and wacko neighbours), a sense of been-there-done-that soon emerges thanks to the film’s blatant unoriginality. Borrowing so extensively from recent hits like Jordan Peele’s Get Out, Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror and Bruce Miller’s The Handmaid’s Tale, all in which its lead characters are forced to live—knowingly or unknowingly—in an oppressive Dystopia of sorts, Don’t Worry Darling is left with little identity of its own to truly stand out or achieve anything groundbreaking.

It’s easy to agree with the many reviews which posit that Don’t Worry Darling is Get Out but repurposed for white women, and it’s true that the maddening, cultish plots of Peele’s hit horror—now so integral to the portrayal of the Black experience in American cinema—finds an uncomfortable echo in Wilde’s film. Yet where Peele’s horror speaks so deftly of racial politics in America, here the film’s attempts at exploring misogyny fall disappointingly flat, with its comments on the domestication of women begin and end with rather obvious scenes of domesticity and beauty. Thus women are boxed into shop fronts sporting vacuum cleaners and nighties, stuck behind mirrors, sandwiched between the walls of their home, and, perhaps the cheapest and most reductive of all versions, clinically insane. Such scenes combine to form a somewhat juvenile, after-school-special representation of oppressed women.

Credit where credit is due, Don’t Worry Darling is visually pleasing enough to be somewhat enjoyed—that is, for the first hour or so of this long and repetitive film which could have packed all its (minimal) punch into 90 minutes or less. So determined is this film to impress that each passing scene is but another setup for Alice (and therefore us) to be overwhelmed with shock, in a tedious merry-go-round structure.

In one of many, many similar moments, for instance, Pugh’s character discerns that a box of her perfectly uniform eggs are in fact hollow, presumably the result of some ‘design glitch’ at Victory headquarters. Perplexedly holding the empty shells up to the light, she crushes each egg in her hand methodically in what we can assume is intended to uncover the fakery of Victory, but which instead becomes a rather unfortunate analogy for the film itself—each scene a perfectly formed, hollow shell, executed time and time again before our eyes.

Doing much of the film’s legwork, and perhaps the only thing really ‘original’ about it, is a strong, hypnotic score from John Powell, which eloquently—if jarringly—epitomises the cultish facade of Victory. But it succeeds in creating a suspense that isn’t really there. Pugh, though highly skilled, bears the brunt of this lack, seemingly compensating with an often exaggerated performance—which is understandable given the little she has to work with here. Styles, though befitting of the film’s mid century aesthetic, is simply miscast.

Don’t Worry Darling winds up becoming a mere excuse for pretty people to don pretty outfits and indulge in (an admittedly gorgeous) 50s aesthetic. The film culminates in what can only be described at best as visually cathartic, doing away with any logical conclusion—and, bizarrely, as Jack’s sudden ghostly appearance at the film’s end would imply, hinting at Alice’s unending love for the abusive captor who forces her to live in a metaverse as she seemingly blasts off into the ether. Quick, just roll the credits!

So much more intriguing, and indeed more sinister, would the film have been were it set in a more tangible world, one centred around the subtleties of misogyny very much alive today, all without the reliance of virtual reality—a childish component which waylays the film from arriving anywhere genuinely interesting. For it’s tapping into the ubiquitous microaggressions which lurk beneath the surface of everyday life and which perpetuate oppression that today’s more attuned audiences want to see. ∎

Leave a comment