Cumberbatch and Dunst shine in Campion’s twisty, brutal exploration of alpha masculinity

*Contains spoilers*

In a pivotal scene from Campion’s Oscar-tipped Netflix comeback, Rose (Kirsten Dunst) clumsily practices the piano for a formal dinner party to be hosted in her new home: the stately, Gothic ranch house she is forced to share with her toxic brother-in-law, antagonist Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch). Irked by her awkward playing, Phil begins to mimic her, note for note, on the banjo from upstairs. Stopping and starting precisely when she does in a taunting, oppressive duet, Phil’s cowboyish banjo playing is at once menacing, haunting and de-feminising. This moment is not only bitterly intense, but powerfully encapsulates the two opposing (and seemingly binary) forces at work in The Power of the Dog: sensitive femininity and virile, toxic masculinity.

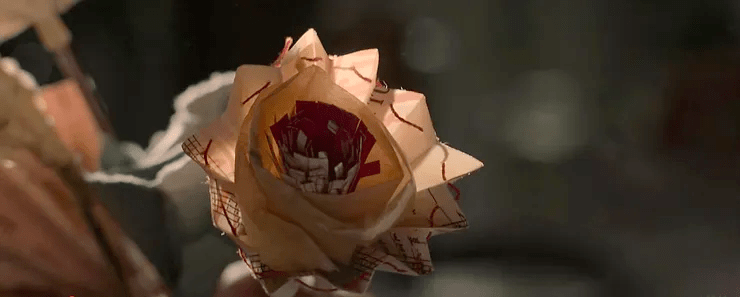

Johnny Greenwood’s oscillating, volatile score, while echoing the hilly barrenness of the Montana mountains, helps establish such a dynamic from the film’s start. Low, typically masculine string notes are used to introduce Phil and his rancher lifestyle while high-pitched, shrill piano chords introduce Rose’s effeminate son, Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), as he crafts a delicate collection of paper flowers alone in his bedroom. These more feminine sounds find visual resonance in the delicate paper flowers, ornaments subsequently used to decorate the tables of his mother’s inn where he works.

Crucially, when Phil and his fellow ranchers dine at the inn on a pit stop from their cattle drive, Phil mockingly admires the girlish crafts, musing “what little lady made these?” When the queer-looking Peter informs him that it was in fact he who made them, Phil pokes fun at his fussy use of a waiter’s cloth (which he drapes over his forearm, waiter-style) before setting fire to a paper flower and lighting a cigarette from the flames. And thus, just as Phil’s musical mocking suffocates his mother’s attempts at piano playing later in the film, Peter’s paper flowers are destroyed in a cruel act of humiliation—a violence heralding Phil’s gradual destruction of his aptly named mother, Rose.

Inherent in the above scenes is a rejection of Rose’s and Peter’s technical ability—namely, Rose’s use of the piano and Peter’s resourceful craftsmanship. From his nimble, one-handed cigarette rolling to the skilled castrating of his cattle, Phil’s dexterity reinforces the virile identity of skilled craftsman and chief rancher he seeks to uphold. Likewise, animal agriculture and the production of leather goods feature heavily in the film to embody a traditionally masculine domination of the land. Graphic shots showing Phil engage in the mutilation and abuse of animals, like his treatment of those around him, as such represent a physical and technical dominance of the land, it’s animals and people.

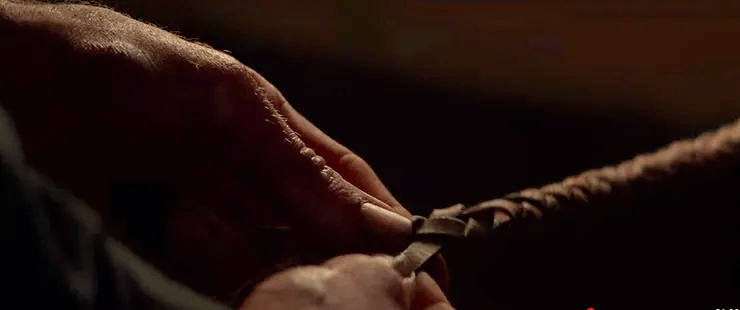

Yet there’s a comical irony to Phil’s swashbuckling persona which threatens to shatter his tough facade. As apparent in cowboy culture more generally, homoerotic/queer undertones are apparent not only in the playful camaraderie of the ranchers as they bath nude, dine out and form close bonds, but also in the delicate, apparently intimate craft of lasso making. And use of leather in the film—in particular, ass-less chaps—has been said to function as a playful nod to the appropriation of leather in queer culture (which close-ups of Phil’s swaggering rear may confirm). Phil’s bravado identity is shattered perhaps most tellingly—and subtly—when Phil masturbates with the handkerchief of his ex-lover and maestro, Bronco Henry. Itself a white cloth, Phil’s use of Bronco’s handkerchief mirrors Peter’s pretentious use of the waiter’s cloth so derided by Phil at the beginning of the film, linking their queer identities and thus closely associating the pair.

Just as Phil possesses a repressed homosexuality, Peter, in a chiasmus of roles, harbours a hidden masculinity obscured by the apparent femininity of his sensitive, “sissy” persona. Consider the very paper flowers which to all appearances reveal to us his effeminate character but which, though delicately crafted, are nonetheless false objects masquerading as flowers. Moreover, the material used for the paper flowers is in fact sheet music for the piano, adding new meaning to the high-pitched piano notes used to introduce Peter as he snips away at—mutilates—the pages. Peter’s mutilation of the sheet music is a subtle act of gender subversion, one at odds with the piano notes used to introduce him and which we assume, like the paper flowers themselves, denote femininity. Notably, Peter in fact makes a trim of the sheet music, mimicking, if not out-ing, the suede trim typical of western cowboy wear. Like the scrapbook he works on, a tapestry of gender-varied clippings from magazines and newspapers, books and other sources, Peter’s crafting reveals a subtle yet telling level of gender fluidity.

Yet most obviously revealing Peter’s hidden masculinity are his acts of animal mutilation, referenced briefly in the film’s opening scenes when Peter is asked to kill three chickens to feed the ranchers that afternoon. This is a brutality conveyed more shockingly later in the film when Peter, in order to develop his understanding of anatomy, mutilates a the rabbit he catches and brings home (and which we’d believed was to be fondly kept as a pet). Yet Peter’s callous treatment of sentient beings culminates, as we know, in his resourceful murdering of Phil via anthrax which he samples from the carcass of a dead cow. Another ironic reversal of roles, rancher becomes cattle and “sissy” becomes cowboy in a deeply symbolic castration of sorts.

Peter’s queerness allows him to navigate, exploit and in so doing collapse the tightly gendered realms of early twentieth-century rural America to his benefit. On the one hand he can partake in the typically feminine arena of arts and crafts, don jeans in an avant garde manner, enjoy a close relationship with his mother and affectionately caress animals; on the other, he can mechanically mutilate rabbits for educational gain or kill them for food, learn horseback, skilfully navigate the treacherous Montana mountains and enrol at college to study medicine. Shrouded by an effeminate persona, Peter furtively wields his medical and ranch knowledge─both typically masculine fields─to murder Phil, thus unveiling a gender duality unique to him. This is a power through which he is able to restore order and save his “darling” mother from the eponymous “power of the dog.”

Peter’s silent power is hinted at too, if not dangled in the face of viewers during the climactic, erotically charged barn scene towards the film’s end. As Phil weaves away at the toxic fringe, demonstrating to Peter the art of lasso making while recounting Brokeback Mountain-esque romances with Bronco, Peter rolls a cigarette. Between takes, Peter flirtatiously places the cigarette in Phil’s mouth for him to draw from, a passivity underscoring Peter’s newfound authority. Retrospectively, Peter’s cocky cigarette-wielding is a subtle rejoinder to Phil’s lighting of a cigarette from a burning paper flower─the rolled cigarette thus book-ending their relationship and crystallising their role reversal.

Moreover, that Phil dies as a result of making lasso from Peter’s anthrax-riddled hide is highly symbolic, not least because his renowned efforts to avoid anthrax parallel his efforts to repress his sexuality. While we at first interpret Phil’s tutorial lasso making to be a metaphor for his mentoring Peter, replicating his own relationship with Bronco, that Peter poisons the hide brilliantly reveals the opposite. A technology intended to catch prey and tighten, one typically wielded by a rancher, the lasso instead places Phil in a self-made trap as his rancher knowledge and skill—both of which he imparts to Peter—is reversed upon him to displace his masculinity. Once again Phil is figured as cattle, and where his cocky, toxic displays of manly prowess are his eventual undoing, Peter’s surreptitious expertise is his making.

Yet with the delicate, inherently feminine appearance of a plaited braid, the lasso, like Peter, becomes a rose-like figure: effeminate but possessing a harmful technology. The poisoned lasso thus becomes a symbol for the technical ingenuity Peter quietly harbours beneath—but which is integral to—his queerness. The craftsmanship of the rose-like paper flowers so derided by Phil is here reversed upon him as Peter utilises his knowledge to remove Phil’s masculinity, an ingenuity mirrored in the trim/braid/lasso. In killing Phil with poisoned hide, Peter frees his mother from Phil’s toxic grasp, acting as a protective thorn to his mother, his R/rose. To quote Marianne Moore when she muses on the thorns of a rose, “They are not proof against a worm, the elements, or mildew / but what about the predatory Hand? What is brilliance without / co-ordination?” ∎

Leave a comment